The true story is even creepier than the song

By Wayne Bledsoe

“I met a little girl in Knoxville, a town we all know well

And every Sunday evening, out in her home, I’d dwell

We went to take an evening walk about a mile from town

I picked a stick up off the ground and knocked that fair girl down …”

If you grew up in East Tennessee, you likely know quite well what happens next in the song “Knoxville Girl.” The poor girl begs for her life before being bludgeoned to death, dragged across the bloody ground and tossed into the river. That Knoxville is the site of possibly the most famous murder ballad in history is a grisly honor. For years, it was the only thing many outsiders knew about the city.

It’s been sung countless times, and it’s been recorded by artists as varied as The Blue Sky Boys, The Wilburn Brothers, The Lemonheads, Nick Cave and Arthur Tanner, who’s 1925 take is the first known recorded version. The Louvin Brothers, however, were responsible for laying down the most famous version of the song in 1956. Through the years, it has only gained in popularity. After spending an afternoon showing Elvis Costello around downtown Knoxville one day in 2005, I watched him perform the song on stage at the Tennessee Theatre.

“… She fell down on her bended knees, for mercy she did cry

‘Oh Willy dear, don’t kill me here, I’m unprepared to die’

She never spoke another word, I only beat her more

Until the ground around me within her blood did flow

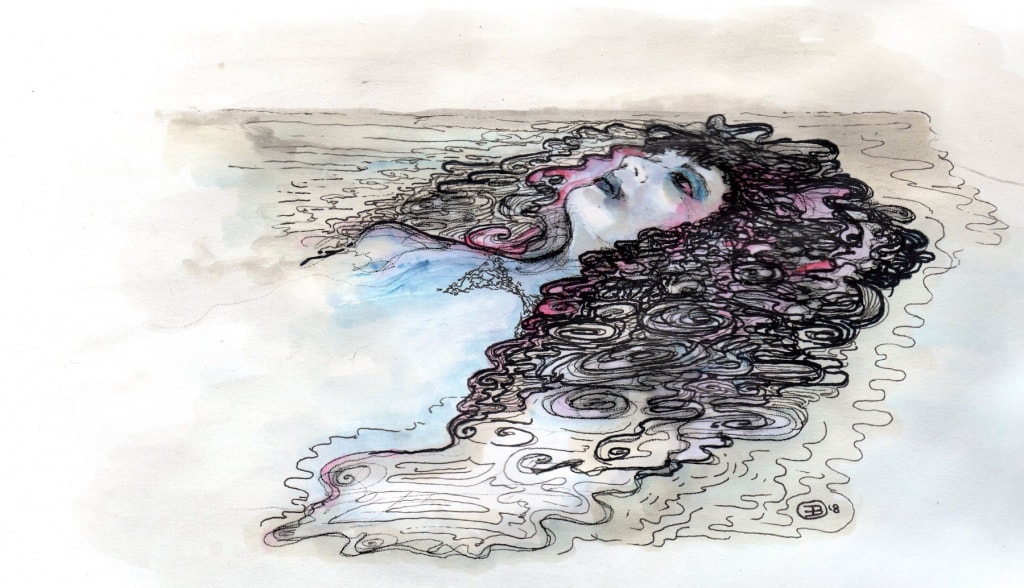

I took her by her golden curls and I drug her round and around

Throwing her into the river that flows through Knoxville town

“Go down, go down, you Knoxville girl with the dark and rolling eyes

Go down, go down, you Knoxville girl, you can never be my bride …”

It should come as some comfort that the murder didn’t actually take place in Knoxville. Until recently, there was only speculation that the song was about a real event at all. It’s been well known that there was a direct link between the songs “Knoxville Girl,” “The Berkshire Tragedy” (an English ballad that dates to at least the mid-1700s) and “The Bloody Miller,” which was first documented in the late 1600s.

In “The Berkshire Tragedy,” the murder only starts with a bludgeoning by stick. The murderer begins by whacking the poor girl in the face, then slits her mouth “from ear to ear” and finishes her off by stabbing her in the head. “The Bloody Miller” is a much longer song, and any number of folk variations (one places the incident in Lexington, Kentucky) have sprung from the various lyrics both in Britain and the United States, with different “Miller” lyrics appearing in them.

In his research for the book “Unprepared to Die,” author Paul Slade finally got to the bottom of the story. I spoke with Slade in 2015 when his book was published and was amazed at what he’d uncovered. The actual murder that formed the basis for the ballads occurred in 1683 in the Shorpshire area of England. The victim was named Anne Nichols, and her murderer was Francis Cooper. A child named Icabod was born to Nichols near the time of her murder and was baptized 23 days after his mother was buried.

Slade found the records in the Shorpshire library’s collection, which contained parish records from the 1600s.

“I was able to go through the village documents and actually find the handwritten version of the two individuals’ names in the old parish register,” said Slade. “That was an astonishing moment. It sounds incredibly nerdy, but just the thrill of actually seeing their names after following the trail that far was just a marvelous moment.”

In “Knoxville Girl,” the reason for the murder is never quite explained. It’s a little clearer in the older songs: The murderer had had sex with the victim but didn’t want to marry her. You might assume that the killer had gotten his victim pregnant, but knowing that a child was actually born from the tryst is a real revelation. Of course, the question then becomes: Did the killer wait until the child was born before murdering the mother, or was the child delivered after her death?

“I guess those are the only two possibilities,” said Slade. “Maybe a living baby was cut from its dead mother’s womb. I guess that’s just about possible. That would’ve been a very, very rare occasion. But Icabod’s name is there. You can’t deny his existence, but I certainly can’t explain how that element of the story happened.”

To understand how and why the song changed, you have to imagine how early balladeers operated. They traveled with new songs, often based on lurid news events, and sometimes another singer would simply remember the song as best he or she could and perform it, passing it on. At other times, the song lyrics were preserved on pages that the singers would sell.

“They knew what sort of ballads would sell, and they brought the same sort of instincts which a tabloid news reporter would bring to these stories,” said Slade. “They always amped up the drama and always brought the most sensational aspects of the story to the foreground.”

While the broadsheets of balladeers have been saved in British libraries, the songs also were preserved by being passed down in communities and families of European immigrants who settled in the mountains of Appalachia. Sometimes the songs were adapted to more current times.

Slade dispelled the speculation that “Knoxville Girl” was inspired by the murder of Mary Noel in Pineville, Missouri, in 1892. The murder (documented from historical sources in Slade’s book) is strikingly similar to the murder in Shorpshire. In fact, balladeers from the time adapted the song to that murder and called it “The Noel Girl.”

“The links between ‘Knoxville Girl,’ ‘The Berkshire Tragedy’ and ‘The Bloody Miller’ are so clear that there’s simply no denying that ‘Knoxville Girl’ began with those two old English songs,” said Slade. “The imagery is the same, and so many of the lines are almost identical in the way they’re phrased. … You can see that once it’s been rewritten as an American song that there would’ve been a desire to find an appropriate murder to pin it to.”

The key element that connects all of the versions of the song, said Slade, is the killer’s bloody nose, which shows up in nearly all of the variations.

“… I started back to Knoxville, got there about midnight

My mother, she was worried and woke up in a fright

Saying ‘Dear son, what have you done to bloody your clothes so?’

I told my anxious mother I was bleeding at my nose …”

It’s the nasal element that makes another murder ballad, “The Banks of the Ohio,” somewhat different, although the murder in that song contains the victim pleading for her life in almost the same way as “Knoxville Girl” (albeit before being stabbed rather than beaten to death) and being thrown into a river. And in this case, it was the murderer who wanted to marry the victim rather than the other way around. But, of course, “The Bloody Miller” had both a bludgeoning and a knife attack, so it’s likely that “Banks of the Ohio” stems from that same 1683 murder, as well.

Slade referred to the bloody nose as the “DNA” that connected “Knoxville Girl” to all its earlier variants. But there’s other DNA that he’d like to know about, too: He could find no record of Icabod after his baptism.

“It raises the interesting possibility that Icabod may well have had children himself and, if there’s a family line that extends into today, that it could be that Anne and Francis’ distant relatives are still around.”

stumbled this song in spotify and it really did give me the creeps!