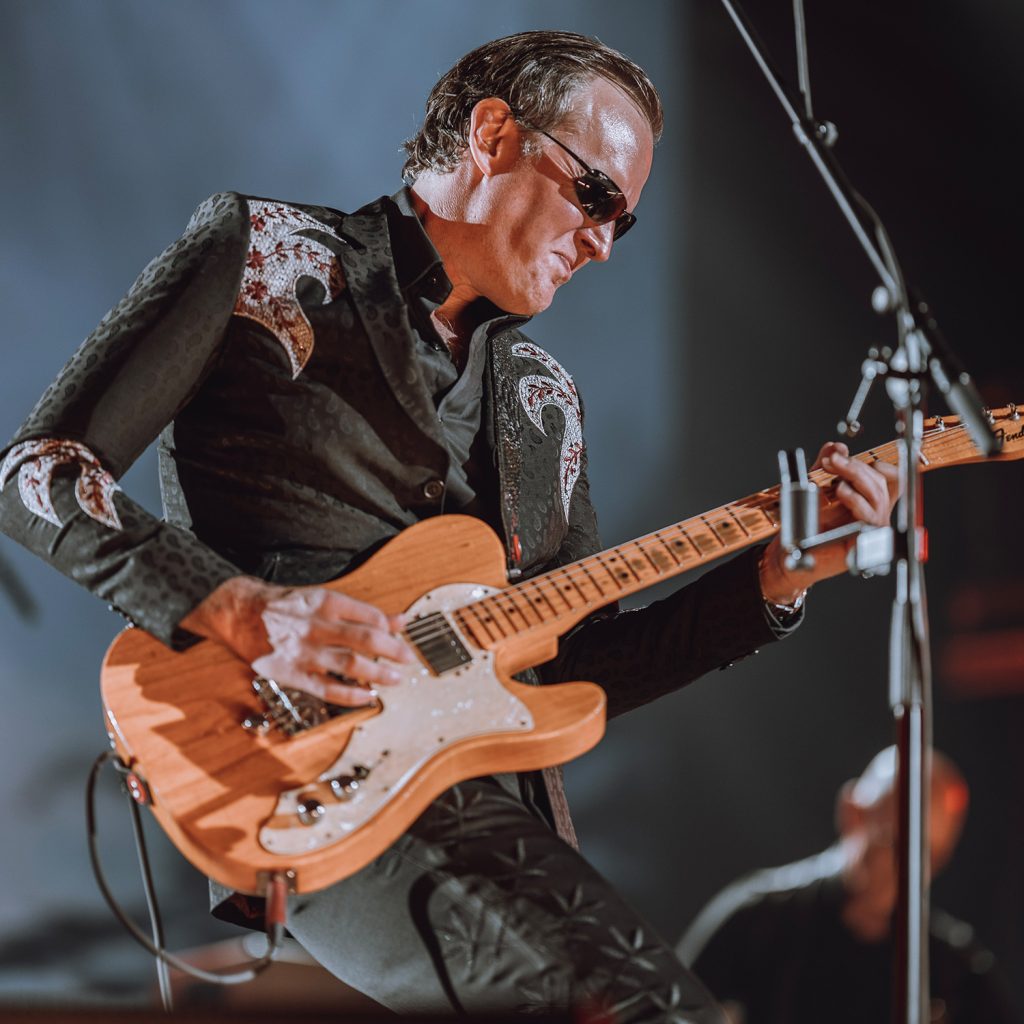

Joe Bonamassa’s name is practically synonymous with the core of modern blues. While he offers abject appreciation for its roots and those that pioneered the idiom early on, he’s made it a point to move the genre forward into the future. Not that he forsakes the past, as his love and admiration for the British artists and icons who led the blues revival in the mid to late ‘60s – artists like Clapton, Beck, Page, Jethro Tull, and Fleetwood Mac – are noteworthy, and he’s made it a point to revisit many of those classic tracks in the company of the provocateurs who recorded them originally.

Two current examples can be found in his recent pairings with Peter Frampton on an old Humble Pie standard and with Dave Mason, with whom he recorded a cover of Mason’s perennial classic “Feelin’ Alright.” Many of the 15 solo albums he’s recorded also have referenced those archival origins.

At the same time, Bonamassa has plenty of reason to rest on his own reputation, as well. Having opened for B.B. King at the remarkably young age of 12, he went on to earn three Grammy nods, score 11 No. 1 albums on the Billboard blues chart and win the prestigious Blues Music Award.

He also runs his own record label (Keeping the Blues Alive) and his own charitable organization, the Keeping the Blues Alive Foundation, which is committed to promoting blues music heritage, funding music scholarships and supporting music education programs. His annual fundraiser, Keeping the Blues Alive at Sea Cruise, has helped the organization significantly contribute to its various educational initiatives. This year’s cruise sets sail from Miami to Cozumel, Mexico, March 18-22 and features Bonamassa, Grace Potter, Marshall Tucker, John Oates and Black Country Communion, the super group that Bonamassa is a part of.

That’s not his only all-star association, though. Aside from the artists with whom he works – Dion DiMucci, Joanne Shaw Taylor, Joanna Connor, Larry McCray and others – on his label, he had a long-running partnership with blues vocalist and keyboard player Beth Hart, which in turn garnered the pair a Grammy for best blues album of 2013. In addition, he’s a member of jazz-funk outfit Rock Candy Funk Party, he produces podcasts and he has sat behind the boards for a number of other artists.

BLANK recently had the opportunity to speak to Bonamassa ahead of his performance at the Knoxville Civic Auditorium on Tuesday, March 5. He graciously shared his thoughts about what prompted his initial inspiration, as well as his current quest to pursue his most intensive muses.

BLANK Newspaper: One of the many wonderful things about your career pursuit is your fondness for England’s blues revival of the ‘60s. We know that early on you were inspired by Clapton and Beck and the other guitar innovators who took American music and transformed it into something unique that brought new listeners into the fold. By reviving the revivalists, you’re certainly doing a service to those that may not have heard that music early on.

Joe Bonamassa: You know, it’s an interesting time to be alive in music. When you look back, we’re all staples of the DNA of the music that inspired us to pick up the guitar in the first place. That certainly can be said for a certain contingent of younger people. You might ask one of them, “Hey, have you checked out Wings? It’s Paul McCartney.” You naturally assume everybody knows these people who are otherwise basically household names. That’s how I grew up. They were household names. It should be like George Washington. But it’s not like that. It’s 2024. Sometimes a remake of a song can introduce a younger generation of people to music that they may not have had put in front of them originally.

BN: So that’s what we mean when we say you’re doing a service of sorts. You bring that music into the modern era. By taking your cue from the interpreters of blues – the modern masters – you’ve made it all the more pertinent. You bring it into the modern era and take it forward from there.

JB: I’m interpreting the interpretations that were done 50 years ago or more. They did it in such a way as to not be doing simply carbon copies. They made it their own. They brought Muddy Waters’ music to a generation of suburban white kids who had no idea who Muddy Waters was, including a young Joe Bonamassa.

BN: It seems now that you are synonymous with blues in its current incarnation. You’re so present. It seems like you’re everywhere these days, at least in terms of influences and output. You’re actually omnipresent in a sense.

JB: I appreciate it, but, you know, it seems like every 10 years, there’s somebody who comes along in the blues. My bar mitzvah moment was in 2009 when I did that gig at the [Royal] Albert Hall with Eric Clapton. So now, 70 years on, here comes Gary Clark and now Kingfish. There’s always somebody that comes along every 10 years who comes up with a new interpretation and becomes the great savior of the blues. And here’s the thing about blues: It’s never gonna go anywhere. Ultimately, it’s just how you interpret it and then make it your own. It’s really that simple. And it seems like it’s a once-in-a-decade event.

BN: You actually anticipated the next question, which is how do you stand out in a genre that has been so exposed and so widely played and so popular? How does one elevate themselves within that spectrum?

JB: There’s a thing you have to do, and that is to not pay attention to the chatter. Because there’s a certain contingent of the blues community that says blues can only be this or it can only be that. It can’t be anything else. But that’s a personal taste issue. I’m not saying it’s wrong, but for it to get in front of a larger, more eclectic audience, you have to f*** with it a little bit. There’s no reason for me to recreate something lo-fi because we’ve gone electric.

BN: Right. There are those folks that resent anything that veers from the template even the slightest bit. They say, “That’s not blues.” So it becomes very straightlaced, and then you have to wonder how you can keep this idiom moving forward.

JB: The real question is: Do they want it to move forward at all? I think the artists that have introduced more young people to the blues than anyone else would be someone like Jack White, even though he did an end-around and never called the White Stripes a blues band. But when I hear early White Stripes, I hear Leadbelly – but just with a punk-rock attitude. With what Dan Auerbach does, when I hear that stuff, I’m like, “These kids don’t even know they’re listening to the blues.” When they’re listening to what they think is current hip-hop music, it harkens back to the Mississippi Delta or even the kind of early electric blues of say, T-Bone Walker.

BN: Aside from being a very prolific artist, you’re also an entrepreneur. You have your own label. In many instances, it’s difficult to attend to both the artistic/creative and business sides of things. How have you managed to navigate that divide between the two?

JB: It’s called the music business. You can’t be an artist that just goes, “Well, I just play the guitar and sing.” You need to know the mechanics of how a business works. If you’re a solo artist or even when you’re a band, you are a brand. It is not unlike Coca-Cola. It’s that simple. How do you market yourself? How do you expand your audience and keep your audience and maintain your momentum? You have to invest in your production, invest in your future. Without marketing, it won’t work. It can’t just be like kids who just sit around and play. That’s what it all really comes down to. That’s a personal thing. The artists that I know do it. But it’s not for everyone. It is what it is. It’s nice to know that, as an artist, you’re financially settled. That opens up a lot of doors for you. It creates a lot of freedom not only for yourself, but for the ability to help others elevate themselves financially, as well.

BN: And as a producer, we would imagine that you have to elevate others creatively, as well.

JB: I know how to get the best out of people and our songs. Even if you’re dealing with a guitar player and you have a great song…That song may have a great guitar solo, but if you have a mediocre song and it’s not sung well, even with a great guitar solo, it’s not going to go the way you hoped for.

BN: It seems like your muse never deserts you. You always seem to have a new project in front of you. So what dictates your next direction, your next project?

JB: I like being a working musician. I’m not just a blues player, you know. I like a lot of different forms of music, and that gets back to what we were just talking about: having the financial freedom. Success in one genre allows me to explore other things that would not have been on the table if I didn’t have success in what I do. I always call that my day job. My life is rocking the funk party. My day job is the touring that we do that allows me the freedom to do what we might not [be able to] afford to do otherwise, the stuff that’s not part of the day job.

BN: It certainly seems like you’ve managed to take advantage of those opportunities. The fluidity of it all is pretty impressive.

JB: If you look at the records that I’ve played on over the years, you might think, “What the hell is this guy?” One day I’m playing with Bobby Rush, and the next day I’m contributing to a new Alan Parsons album. Actually, it could be the same day. The opportunities are more immediate, especially in the modern era. The days of having to be in a room to do these collaborations is kind of an anomaly. You can email your part on an mp3. It still sounds like everybody is in the same room. A lot of times, if I have three or four of these things stacked up, I’ll just go to the studio for a couple of hours and be like, “OK, now here’s my part for Bobby Rush.”

BN: Your ability to multitask is quite admirable.

JB: One of the things that I learned in my youth is that you want to be able to speak all of the languages. In our show, we go from straight blues to borderline progressive. And you can only do that with a band that speaks all the languages.

BN: Obviously, you’ve played Knoxville before, so what are your thoughts about the city? Has it made an impression on you?

JB: I always like coming to Knoxville. It’s a great city. I’ve technically been a resident of Tennessee for eight years, so it’s always nice to feel the support I’ve had between Knoxville, Chattanooga, Nashville and Memphis. Those are regular stops on our tour. And so it’s always nice to come to those places and play gigs, especially when it’s your adopted home state and you have people who really like what you do. I know there’s been an influx of carpetbaggers from California like me over the last decade.

BN: So what brought you to Nashville eight years ago?

JB: Just from the point of the logistics, Nashville makes more sense. We used to have to rehearse in California and then send the trucks from Nashville to California to pick up the gear, and later send the trucks back to California to store the gear. Plus, I was writing a lot in Nashville and staying in hotels, and so as far as finances go, it was just becoming weird and untenable. The first step was to move the rehearsing there and then the gear. Some of my solo records and the productions that I do were already being done in Nashville. So it made a lot of sense just to buy a place and set up shop.

BN: It is centrally located, that’s for sure.

JB: All the tour buses come from Nashville. So it takes a flight out of the equation and just makes sense on a plethora of levels.

BN: Do you still like touring? Many artists say, “You pay me to travel, but when I’m playing onstage, I’m playing for free.” Is that how you feel, as well?

JB: If an artist says to you, “I really don’t like to travel,” then it’s not the touring that they don’t like. If you don’t like to travel and you don’t have that nomadic gene in you, then touring isn’t for you. I do know some people that are out there begrudgingly because the only way to make real money is to play live shows. The mailbox money is pretty much a thing of the past. So that’s really the one way of doing it. But I also think your audience can sense when you don’t want to be out there.

I like touring, and for this reason: We could play a great show the night before Knoxville, but it doesn’t mean we’re gonna play a great show in Knoxville the next night. So you start at zero every day. Even though it’s the same stage with the same gear and the same PA and everything is relatively the same, you still start at zero and then try to get into 100 percent every day. And that’s an adventure and a discipline in itself.

BN: But I’m sure you’d agree that it also has its drawbacks.

JB: It’s a grind to live out of hotel rooms every day. If you’re five weeks into a six-week tour, you always say that it runs a week too long. But then the minute you get home four days later, you miss the action. I’ve made friends all around the world. We’re going to Brazil this year. I know people in Rio. I know people in Sao Paulo. I know people in London. I know people in Hong Kong. I know people in Australia. And it’s like the only way you get to make those relationships. It’s not like being on Instagram.

And I’m looking forward to playing in Knoxville…At the beginning of December when we shut down, I was saying I really could use the break, but now, a month and a half or two months later, I’m like, “Let’s fire things up!” If you’re a lifer, that’s how it works.

lee@blanknews.com