In a neighborhood where time has shuttered windows and weathered every sign, one door still opens five days a week, just like it has for more than 70 years.

Some places endure not because they’re needed, but because someone refuses to let them die. Barnes Barber Shop is one such spot, and Ernie Barnes is the reason.

He and his daughter, Debby, open the shop at 8:30 a.m. each morning, just the two of them now in a place that once hummed with the sounds of dueling clippers, clacking scissors and multiple conversations taking place at the same time. These days, the silence within gives way to memory, two of the four chairs out front filled with stuffed animal placeholders, everything tinged with the faint yellow of age.

Despite the fact that the Burlington community, home to Barnes Barber Shop since 1951, is a crumbling version of what it used to be, the shop’s loyal customers still come here for a haircut. They stopped offering shaves during the COVID pandemic, and the three or four shoeshine boys who rubbed out scuffs for the customers in the shop’s heyday have been gone even longer.

The calendar is still full of regular appointments, however, and there’s something reverent and reassuring, they say, about the way the chairs they sit in creak and groan with age, the way the decor preserves the history of this business and this part of town, the way the hum of clippers rises like a familiar song.

On a recently dreary Wednesday in early May, they buzz out an electric rhythm as they help sculpt Capt. David Frazier’s flattop, the hands holding them spotted with age and lined with veins beneath wizened skin that resemble a road map.

They’re old man hands, and Ernie will be the first one to say it: He’s got more years behind him, a lot more, than he does in front of him. But as long as the customers who have come to this shop since 1951 keep returning for a trim, he’ll keep manning his chair.

It is, after all, who he is. What he does. What he’s been doing since his father sent him to barber school when he was 15 years old, and his younger brother, Bob, a few years after that.

The Barnes family lived just a few streets away from the location where Ernie and his dad would build a barbershop from the ground up after being discharged from the U.S. Navy and returning to the thriving, vibrant East Knoxville neighborhood where Barnes Barber Shop would become a fixture.

Today, Burlington is a crumbling relic of what it once was. Aside from the motorcycle club – State Burner’s MC – across the street, every storefront on both sides of this end of Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue is boarded up and dilapidated, slowly fading artifacts of a time long gone … except inside the barber shop that stands as one of the last, and in the memories of the man who can’t begin to even estimate how many heads of hair he’s cut over the years.

“I wouldn’t have the least idea,” Ernie says. “I couldn’t count that high.”

“I wish I had a penny for every one he did, though!” interjects Debby. “I wouldn’t want much. Just a penny … but I’d still be rich!”

Now in her 60s, she’s worked for her father since 1980, after an attempt at business school turned out to be a flop. She laughs at the thought of how her mother – Helen, who died in 2018 – who been an executive secretary, was convinced that her baby girl was destined to work the grill at McDonald’s unless she learned a proper trade. Business school, however, disagreed with her temperament, and after attending long enough to get certified as a file clerk, she returned home one afternoon and announced that she had quit.

“I told my mama I’d rather shovel s***t” – and just like the Southern lady she is, she censors herself rather than say the obscenity aloud – “… at the zoo, and she told me to go downstairs and wait until daddy got home,” Debby says. “Well, when he did, she hollered for me to come to supper, and when I did, she said, ‘Tell your daddy what you told me.’

“So I did! And then he said, ‘What do you want to do?’ And I told him, ‘I want to go to barber school and work for you!’ Well, he took me to barber school, and I took to it like a duck to water! Mom said, ‘It’ll never work,’ but I’m still here!”

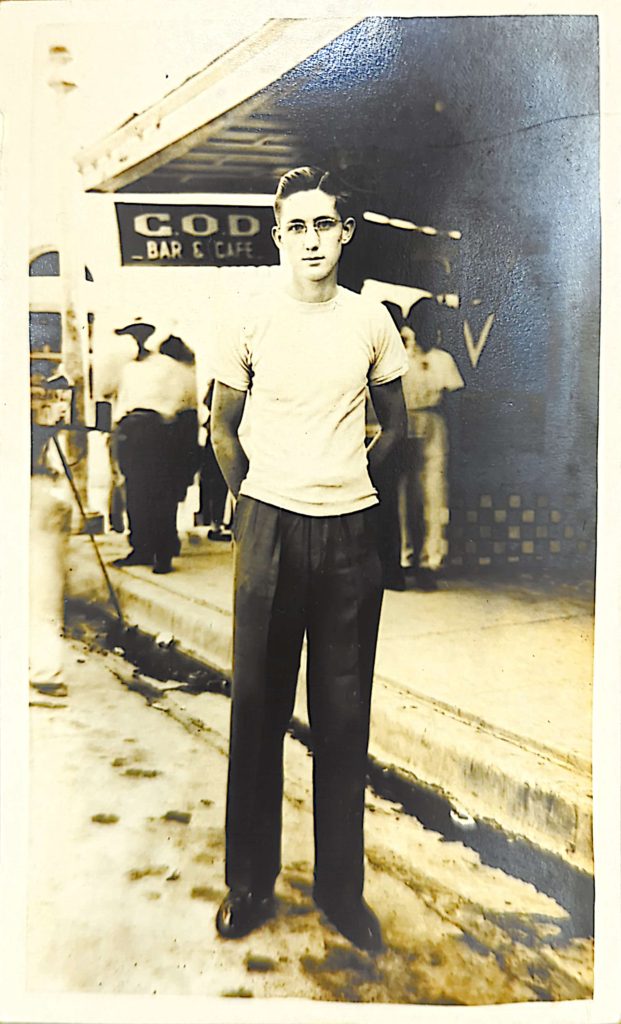

Staying put runs in the family, it seems … as does cutting hair. Ernie’s father, Robert C. Barnes, was a barber along with his brother, and he owned a shop down the street from where Barnes Barber Shop sits today. Although barber school fine-tuned the talent that clearly runs in the family, it was the U.S. Navy that gave Ernie the opportunity to thrive.

Not at first, though, as Debby says. When he saw how the government was drafting every able-bodied 18-year-old, Ernie volunteered at 17 to go ahead and get it over with. As World War II came to an end, his first duty assignment was chipping paint and then repainting a soon-to-be decommissioned ship – not exactly the most glamorous job for a teenager.

“That’s when Daddy decided he was going to do something,” says Debby, sitting in one of the two permanently unoccupied barber chairs in the front room of the shop.

Ernie sits in one of the vinyl seats where the clientele sits, reading the newspaper and greeting customers who come through the door. He knows most of them by name, and despite his age, he still has regulars who are willing to wait.

“I’ve been coming here for 15, 20 years,” Frazier says, who strolls in during the rare interview Ernie and Debby grant to the media. A captain with the Knoxville Fire Department, he stops by weekly for a trim, and Ernie is the barber for whom he waits.

“You find somebody who cuts a good flattop, you keep them,” he remarks.

“That’s his specialty,” Debby adds, returning to the story of her father’s war-era service. “Anyway, after they decommissioned that ship, he went over to the next one and walked on board. They asked him who he was, and he just said, ‘I’m the barber!’”

That ship, Ernie says, was the USS Blue, an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer (and the second Naval vessel to carry that name, after the original Blue was scuttled after being damaged in the Battle of Guadalcanal). Whether it was an official Navy assignment or one Ernie simply walked on board and claimed, he remembers it clearly.

“The captain called me up to the ship the next morning wanting a haircut, and he told me, ‘I’m going to pay you a quarter, 25 cents,’” he recalls. “He said that the officers and the enlisted men would all be giving me a quarter, but he never said what to do with all those quarters, and I didn’t ask anybody. I just put ’em in my pocket.”

While it would be another year before Japan officially surrendered, most of the fighting, at least as far as the Blue was concerned, was over with during Ernie’s time on board. He remembers ports of call in the Philippines and as far away as Shanghai, but he just shrugs when asked about them.

Did you enjoy seeing those places? “Not really.”

Were you homesick? “Not really.”

Say this for Ernie Barnes: He doesn’t say much, and his humility won’t let him brag about his shop’s longevity or the influence he once had in Burlington back when it was a burgeoning alternative to downtown Knoxville – which might as well have been on the moon for all of the need anyone living in Burlington had to travel there.

How Burlington got its name remains a mystery. Jack Neely, executive director of the Knoxville History Project (KHP), long-time columnist for the now-defunct Metro Pulse and the unofficial historian of the city, wrote about the neighborhood frequently, and a 2020 piece for the KHP website detailed a number of theories about the nomenclature.

“People often assume it was in honor of a Mr. Burlington, perhaps an early farmer … to my knowledge, though, no one named Burlington ever lived in the neighborhood,” Neely wrote. “As a surname, it’s very rare in the Knoxville area. Still … the decades have produced several theories. That someone from Burlington, North Carolina, moved there. Or that someone from Burlington, Vermont, moved there. Or that they had some retail connection to Burlington Coat Factory.”

Regardless, in its heyday, Burlington was an oasis for those who wanted to take the trolley from downtown proper to the vibrant little neighborhood on the east side, where Knoxville residents came for rest and recreation even before Barnes and his father built the barber shop. Cal Johnson’s Racetrack, which would be developed in 1921 as a residential area called Speedway Circle, was “the most popular horse-racing destination in the county,” according to Neely, and in 1910, the racetrack hosted the region’s first airplane landing.

It was in this area where Robert C. Barnes opened his own barber shop, but while Ernie was away in the Navy, the elder Barnes had a “nervous breakdown,” Ernie recalls, and ended up selling it. When Ernie was discharged, though, Robert Barnes was determined to make sure his boy followed the family tradition. The first iteration of Barnes Barber Shop was located on Fern Street, a few blocks to the south on the other side of Speedway Circle. The building’s owner rented it to Ernie in 1947, but when he saw the young veteran was doing well, he started raising the rent, Ernie says.

“I started out paying $15 a month rent, and he got me up to $20, then $25, and finally he doubled it,” Ernie says. “That’s when I decided to do something.”

His father co-signed for a loan for $5,000, and together, the pair found a used-car lot for sale where the shop is located now. They built the new shop by hand, four chairs in the front and one in the back, and the men who commanded them were legends. There were the Barnes brothers, of course. Then there was “Big Roy” Estes, a holiness preacher who had the chair in the back and would retire several decades later after a couple of car wrecks left him in too much pain to continue; Shelby Fox, whom everyone referred to by his last name; and “Little Roy” Berrier, a Baptist preacher and a cut-up who transformed into a serious man of the Word on Wednesdays and Sundays. He joined the crew in 1960, a few months before Debby was born. Robert C. Barnes would even fill a Saturday shift on occasion, and just as Debby gets to work with her pops, so, too, did Bob and Ernie with theirs.

Time, however, would eventually claim them all, whittling the crew down to the current two. Fox died first, followed by the Roys – Big, then Little, and finally, back in 2017, Ernie’s brother.

It was a cruel blow, but even then, he never thought about closing shop. And for the men (and some women) who continue to get their haircuts there, that’s a blessing because, while there are other barber shops around town and even more assembly-line haircut joints that sell style more than substance, Ernie and Debby offer something different.

Yes, they cut hair, but they’re also the timekeepers of a part of East Knoxville that boasts a steep history.

They remember it for folks who experienced it with them, guys like Tom Heck, a football standout from Holston High School, class of 1971, and a teacher-coach at Rule, Doyle, South-Doyle and Knoxville Central over the years. He, too, grew up in Burlington, got his first haircut at Barnes Barber Shop when he was 2 or 3 years old and used to come down and listen to the older men and all of their customers, some days packed in so tightly it was standing-room only, tell stories and spread gossip.

“It was a community center!” Heck says. “You came in here, and people were talking about all kinds of different things. I knew to behave, too, or he’d call my mama, and when I got home, I’d be in trouble.”

“Everybody knew everybody,” Debby adds. “You couldn’t get away with nothing!”

Not even a stroke: Tom’s father didn’t get his own hair cut at Barnes until the 1970s, but once he made the switch, he was a regular – so much of one, in fact, that when he didn’t show up for a few days, Ernie or Debby called Tom, concerned.

“I called my brother-in-law, and he went to the house, and he’d had a stroke,” Tom says. “Not a major stroke, but enough of one that when he didn’t show up after coming and seeing them all the time, they were worried.”

At Barnes, the camaraderie extends far beyond haircuts. It’s about presence and how, when someone stopped showing up, it was noticed, and folks acted.

“We were kind of like family,” Debby says matter-of-factly. “We all checked on everybody and made sure everybody was OK.”

As the years passed by, however, more and more of Barnes’ customers stopped coming around, and he would discover why as he read the morning paper and saw their names in the obituaries. For every one that died, fewer and fewer new ones came through the door to reserve a spot, and business gradually began to slow down. The shoeshine boys, three or four of them in the 1950s and ’60s, were some of the first to go, followed by the Saturday hours that gradually shrank back from 6 to 5 to 4 to 3, where it holds today.

Outside the door, the neighborhood followed suit, but what a glorious spectacle it was back then. Get Ernie going, and he can remember with vivid clarity what Burlington once looked like when the shop first opened.

“Over there to the right, they had a feed store, and not long after, they built Ruby’s [Coffee Shop],” he says, referring to the longtime diner that opened next door to Barnes. Up and down the weirdly angled intersections and catty-cornered thoroughfares, everything local residents needed was available, and such convenience made for a flourishing community, Debby recalls.

“We had a grocery store, hair salons, bars – Slick’s Tavern was around for a long time,” she says. Run by Orville C. “Slick” Johnson, Slick’s was a Burlington mainstay for 45 years.

There was a shoe store, a fire department substation, pool rooms and the establishments of other men who, along with Ernie, were considered the de facto business leaders of Burlington: Lonnie Keeton, who owned Keeton’s Jewelry Shop until it closed in 1983; Blaine Farmer, who ran Farmer’s Hardware; Robert Pass, who owned and operated with his wife, Daphna, the Pass Five Ten Store, which later become Pass Clothing, for 50 years; Bill McCarty, proprietor of the place, McCarty’s Mortuary, where folks in the neighborhood sent their dead for last rites; and the Rev. John Buell, pastor of McCalla Avenue Baptist Church, which merged with its parent church, Bell Avenue Baptist, to form Chilhowee Hills Baptist Church in 1984.

Incidentally, 1984 was the year “Footloose,” the Kevin Bacon vehicle about an oppressive small town that forbids dancing, was released. Fourteen years earlier, Buell was quoted in The New York Times during the 1970 Southern Baptist Convention as an outspoken opponent of “social dancing.” (“Any man who says he can dance and keep his thoughts pure is less than a man, or he is a liar!” Buell declared at the time, speaking against a decision by Carson-Newman College administrators to change the school’s charter in order to allow spring dances.)

Hanging on the wall at Barnes is a photo of the six men during their prime, some 40 years back at least, each one looking dapper in coats and ties and Bryllcreemed hair they likely purchased from Ernie after a trim and a touch-up.

“You could buy anything you wanted here in Burlington then,” Ernie says. “Nobody needed to go to Knoxville!”

There was Greenlee’s Drugstore and of course, the Gay Theater, a 278-seat movie house built the same year as downtown Knoxville’s Tennessee Theatre. It would close in 1958, transition to a bowling alley for some years, and was torn down more than a decade ago. Ernie remembers sneaking off to watch serials, cartoons and other showings there.

“We lived on top of the hill, and we’d slip off on Saturday afternoon,” he says. “It cost about 9 cents, and we couldn’t see but one because we couldn’t stay long. We had to get back up on the hill before we got caught.”

The Burlington Fish Market, Lema’s World Famous Chitlins, the Burlington Flea Market. Doctor’s offices, dentist’s offices, banks. Burlington had it all … and now it’s all gone, save for The Lunch House, which opened in 2010, and the Save A Lot, both over on Holston Drive.

“These people, these owners, when they died out, nobody took over their businesses,” Debby says. “When Norman Wright sold the IGA, that hurt it, too. And then when East Towne Mall [later Knoxville Center, now an Amazon fulfillment warehouse] opened, that was pretty much it.

“It just sort of happened, and we just stayed. We like to joke that we’re going to turn the lights off when we leave Burlington.”

When that might be is anyone’s guess. Ernie says he’ll retire when he turns 100; Debby says she won’t let him. (“He can sit right there in that chair and watch me cut hair!”)

Not that the long goodbye to the neighborhood that once was a bustling sub-metropolis matters much to Ernie.

“I don’t pay no attention to it,” he says. “I don’t care. I ain’t got much longer to go anyway.”

It’s not that Ernie is a pessimist; he’s a realist, about as real as a man can get when he’s staring down almost a century of living and has forgotten more wisdom than most folks will ever collect. Take the price of a haircut, for example. When he first opened, they cost 75 cents each (70 cents for kids). In 74 years, they’ve gone up to just $8, and folks still can’t believe that’s where Ernie plans on keeping it.

“Everybody always asks, ‘Why don’t you go up?’” he says. “Why? Everything’s paid for. Doing good is hard to beat.”

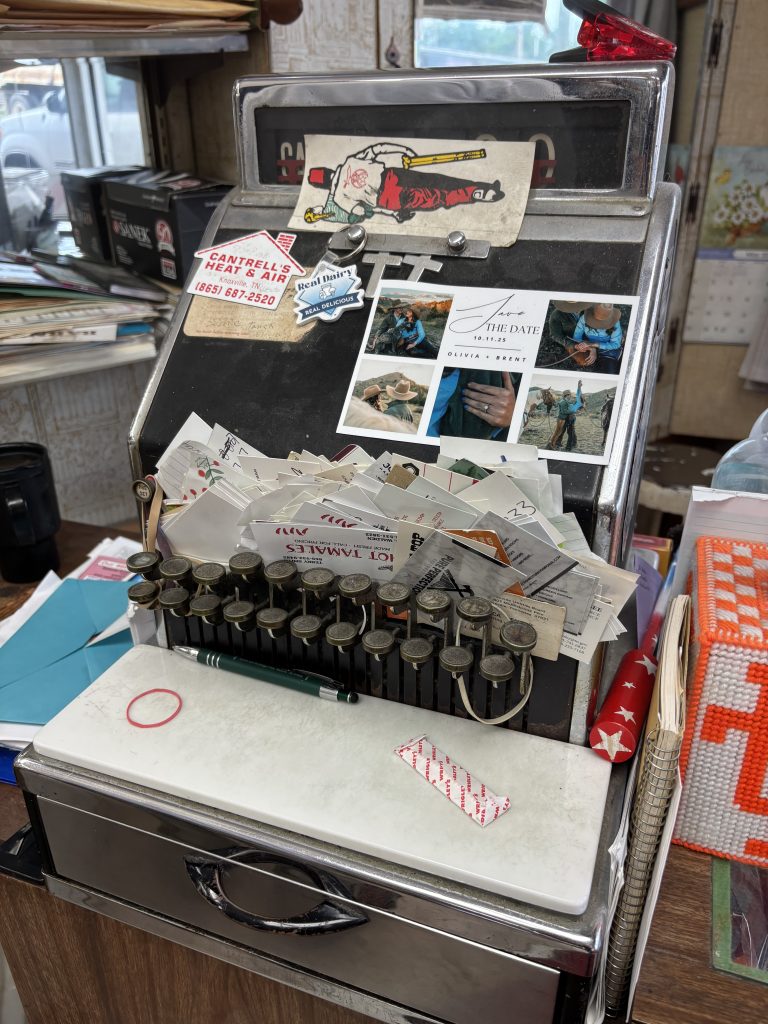

Just be sure and bring cash. Others still ask why he doesn’t accept credit cards, and the reason is simple: “We count our money,” Ernie says.

“It just makes everything else go up,” Debby adds.

If you happen to forget, however, the father-daughter team might let you slide. Tom’s been in there plenty of times, he says, when a haircut is given, and the customer has forgotten the cash-only rule or left his wallet at home.

“I’ve seen them tell people who don’t have money, ‘You can pay me the next time you come in,’” Tom says.

Debby just shrugs.

“Honest people, they remember,” she says.

Such generosity of spirit isn’t forgotten. Flattop finesse aside, Frazier would occasionally bring his triplet daughters in while he got his ears lowered. They’d sit contentedly in their carseats, and as they got older, Ernie and Debby let him set up a portable playpen in the middle of the floor. Today, they’ll run up to “Aunt Deb” and give her a hug before scooping up those stuffed animals and disappearing into the back to play.

“Tell me,” Frazier says, “what kind of place still does that these days?”

The short answer: not many. And between that kind of customer service, the novelty of a 98-year-old barber who still cuts hair and the time capsule of a once-glorious neighborhood contained within the building’s four walls and in the memories of the guy who built it, Barnes Barber Shop is one of a kind.

Even today, as younger barbers open slick, Instagrammable shops with neon signs and curated playlists, Ernie and Debby cut hair just like they always have: with intention, with care, and with an abiding sense of place. The yellowing linoleum floor, the fading photos on the walls and shelves, the crackled barber chairs that creak when customers sit down – they’re not just relics, they’re anchors.

Anchors for men like Tom, who grew up on the stories swapped in these chairs. Anchors for the older customers who still count on Barnes Barber Shop and its two barbers for conversation and levity. Anchors for the few younger patrons who come because their grandfathers did, who find something appealing in the way the sanctity of tradition here slows down an ever-quickening pace outside these walls.

What will happen when Ernie reaches 100 remains a mystery, but Debby knows one thing: She can’t do it by herself. The customer base is still too full, and when she had an emergency appendectomy a few years ago and her dad had to hold down the fort alone, he was adamant after she returned that neither of them would ever, ever, work solo.

What Debby will do doesn’t concern him all that much, he says. Few things do.

“Being a 98-year-old man, I don’t have to worry too much about any of it,” he says. “My time’s getting short.”

For now, however, he’s still here. Still cutting. Still telling stories. Still keeping time in a place that refuses to let go … because Ernie Barnes never has.

wildsmith@blanknews.com

Very well written, fascinating subject. Steve Wildsmith needs to write a book!

I was a customer of Barnes Barber Shop as a kid. 65 years ago. Very well written article. This is the way journalism used to be. It is a lost art.

Beautifully written…beautiful family…this is America!

This is a fantastic piece. The subject matter makes you take deep breaths and stroll down memory lane, and it is exquisitely written. Thank you for sharing, and Godspeed to Mr. Barnes!

What a lovely story.

I used to go to Mackey’s over in Marble City from the time I was in high school until well after we’d moved away. My great grandpa was a barber and still cut hair into his 90s. LOVE to read these kinds of stories.

I’m 76 and I had my first haircut at Barnes Barbershop. My dad took me there all through the ’50s and ’60s and I continued going there with my son through the 70s until we moved away.

When I saw this article I was amazed. I was so glad to see that Ernie was still there. I’m sorry to hear that Bob passed on. I really enjoyed hearing all those stories that I heard there over the years.

Greg Shipe