Knoxville’s great novel invites and rewards re-readings

The Cormac McCarthy Society held its annual conference in Knoxville October 3-5. The city that looms so large in one of the author’s most celebrated novels seems like an obvious place to stage such a thing, but in fact the conference staggers around the globe, and the last time it was held here was 2007.

Even if you consider yourself a die-hard McCarthyite, you might not have known this was happening that week. With titles like “’No avatar, no scion, no vestige of that people remains’: The Posthuman Ecosophy of Cormac McCarthy” and “Narrative Design and Substantive Variations Between McCarthy’s ‘Blood Meridian’ and the ‘Western Novel’ Draft of its Opening: A Reassessment,” the conference sessions aim for an international academic audience. Plus it wasn’t cheap to attend.

Fortunately, organizers like UTK’s Dr. Bill Hardwig recognized the interest of many lay readers of McCarthy in the region and arranged for the keynote address by novelist Ron Rash to be free and open to the public. Rash and his Appalachian-set novels are also popular here, and there was a full house at the East Tennessee History Center for his talk, “Traversing Appalachia With Cormac.” (That direct title goes down a bit easier, doesn’t it?) Rash managed to make it over from his home in Western North Carolina, where he teaches, and pre- and post-lecture conversations seemed to center on the recent devastation wrought by Hurricane Helene. It was kind of hard to talk about anything else that week.

Rash has an easygoing presence and is an engaging speaker. The first part of his talk focused on McCarthy’s influence on him personally and on other Southern writers, and then he read from McCarthy’s novels and his own work. He ended with a long-form poem that imagined Lester Ballard of “Child of God” among the colorful denizens of a dive bar blaring Lynyrd Skynyrd.

One moment in Rash’s talk stood out in particular, something I’ve always sensed and admired in McCarthy’s work but have never been able to articulate. Rash spoke of how McCarthy knows it’s never a good idea to give your villain a backstory because it takes away from the deep-rooted, atavistic nature of evil. (I’m paraphrasing here but think I’m in the general ballpark; apologies if I’ve misrepresented what was said.) If we’re told Anton Chigurh of “No Country for Old Men” was beaten by his father, we might then believe this goes a long way in explaining his cruel and violent nature. This is not an acceptable narrative of philosophical position for McCarthy. What past events could possibly explain Judge Holden’s monstrous behavior throughout “Blood Meridian?” The Judge, one of the great villains of American literature, embodies a preternatural and cosmic evil, and giving him a backstory would dilute that idea.

That’s a difficult notion for some to reckon with, especially in a culture increasingly besotted with comic book logic, but astute McCarthy readers understand how this makes those novels viable and timeless, attuned to an uglier but nonetheless ever-present aspect of our world.

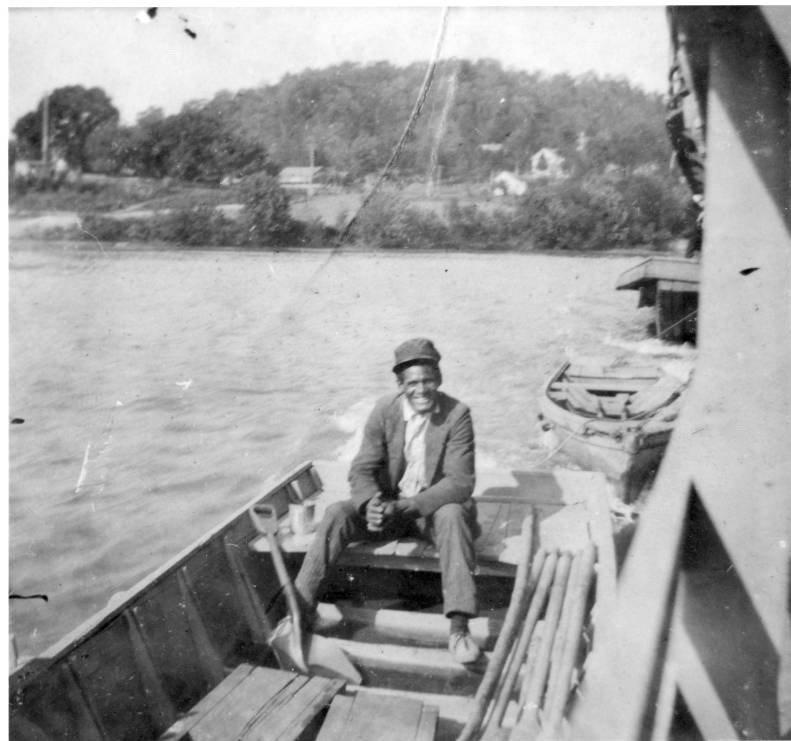

The timing of Rash’s appearance was fortuitous to me. A few years back, I made a film based on “Suttree” using archival footage and photographs from the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound and the McClung Collection. It’s been staged twice, with different edits: once at the Bijou and once at Lakeshore Park, with musicians live scoring it each time. I was invited to screen it again at the Southern Festival of Books in Nashville the last weekend of October. Rash will be reading text from the novel between sections, and William Tyler will live score it.

So I’ve dipped back into the book for the umpteenth time and, as I always do, am finding new things to marvel at and chew on. This time I was assisted by the annotations of an anonymous author who made comments in the margins of a used copy I recently purchased, at times calling my attention to things I might not have otherwise paused and reflected on. “In flight from self-knowledge,” the commenter wrote on page 282, though that observation would not be out of place on many pages of this book. “He stops liking her because her body changes?” they mused after Suttree’s romance with Joyce turns sour. “The fish don’t know the difference,” underlined in a passage after the Goat Man objects to running fishing lines on Sunday.

I know some people get tired of hearing about McCarthy and “Suttree” so much. Knoxville is not a big place, and we only produced a handful of major cultural figures that we keep returning to. But for many of us, the book is an endless reservoir of inimitable poetic prose and useful insights into the human condition.

I enjoy marginalia in general but have a special fondness for seeing it in “Suttree.” So I’m compiling “The People’s Annotated ‘Suttree,’” a collection of notes written in previously owned copies of the novel. I’ll be on the lookout for copies whenever I’m in a used bookstore, and if you happen to find one during your rambles, I would welcome a look. You can find me at the East Tennessee History Center.