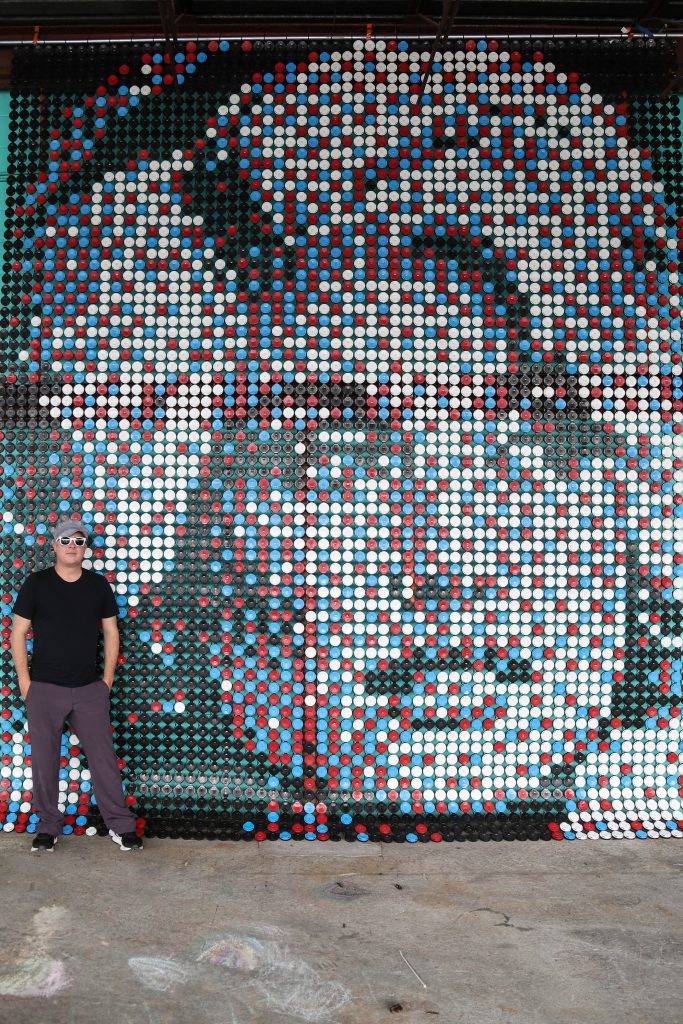

Massive Parton pixel art adaptation on view at Central Filling Station

Already well-known and highly regarded around town in equal measure for his bartending acumen, onstage charisma and buoyant temperament, Dave Bowers now can add respected artist to his list of personal attributes – although he had to wait longer than he would have expected for the kudos to start rolling in.

Though he had been creating art in several mediums for a number of years before he secured his first official show, that scheduled premiere was to mark the first time that he would share his work with the general public. Unfortunately, the installation occurred on March 9, 2020, less than a week before COVID-19 forced the hasty closure of most nonessential businesses.

“My art sat in Kaizen for about eight months, and no one got to see it,” Bowers says, chagrined. “I was joking with my friends, I was like, ‘Welp, first time I let people see my art, the world shuts down!’”

Bowers has dabbled in abstracts, collages, black-and-white shadow pieces and various other forms, but it was pixel art – spurred by a combination of a childhood spent playing Sega and Nintendo video games and a later interest in the visual works of David Lynch – that allowed him to indulge his imagination and fully express himself creatively. Transferring images of Laura Palmer, the central character of “Twin Peaks,” he had rendered via four different graphic-design computer programs into acrylic paintings using a wooden dowel, Bowers was able to construct technically precise pieces that were arresting in their inventiveness and surprising in the humanity they suggested.

From there, Bowers moved on to another iconic figure, this one the preeminent standout in this region’s collective unconscious: Dolly Parton. Using a famous 1977 public-domain photo of the country star as the foundation, his 8-bit interpretation – “It’s totally analog,” he notes – of the pride of Sevier County took an estimated 40 hours to complete and became the first painting he sold. Featuring a black background, it consisted of only three other colors painstakingly stippled onto the canvas.

“Dolly symbolizes America to me, so I figured red, white and blue would be a good way to go,” Bowers says.

Citing hospitality jobs that have provided him access to refuse materials and “so many hours of boredom,” Bowers explains how the next evolution of the Parton painting came to pass by referencing a substantial mandala – a traditional discipline that involves geometric and hex patterns along with straight lines – which he made and that hangs on a wall in his home. The 4-by-4-foot design in the shape of Majora’s Mask, an item from The Legend of Zelda, was created with 1,800 leftover corks that he had procured while working at Chesapeake’s. When his good friend Charles Ellis, the manager at Central Filling Station, hired him to tend bar at the beer-only establishment and he realized just how many canned brews with Pak-Tec closures were being trucked in on a regular basis, the wheels began to turn about how best to utilize the plastic tops in a project. And given Parton’s huge presence in East Tennessee, she seemed like the appropriate subject for a large-scale adaptation of one of his works.

“I saw all those colored Pak-Tecs we get as pixels, and I thought, ‘I can do something really big with these,’” Bowers says, describing how he considered various possibilities of how to assemble the piece before finally determining that the best way to go about it was to cut and affix portions that would hang on the background. “Thousands and thousands” of heavy-duty staples hold together each of the 10-by-10-foot background sections, 42 in all. The colored segments that form the actual design “hinge off of each other, so it moves in the wind,” he explains. “They’re not mounted on anything other than themselves.”

Each background section alone took at least half an hour to build, with between 300 and 400 hours going into the finished product, which weighs about 150 pounds. Commercial zip ties and ratchet straps anchor it to a horizontal metal fence railing, which Bowers concedes was not easy to secure to the rebar lacing on the underside of the food truck park’s protective awning.

He credits Garrett Thomson (another polymath who exhibits many talents) for helping to hoist the structure and attach it. He also thanks Margaret Stolfi, the general manager of the Mill & Mine, for allowing him to check the initial accuracy of the layout by spreading out the sections on the floor of the venue and inspecting them from the mezzanine. Because his conversion math was correct, no adjustments needed to be made before it was installed.

“If I’ve got enough of anything, I can do something with it,” Bowers says about his unique artistic vision, which prioritizes reusing items that otherwise might be deposited into a landfill. Summarizing his process, he concludes, “I use math and garbage to make beautiful things.”