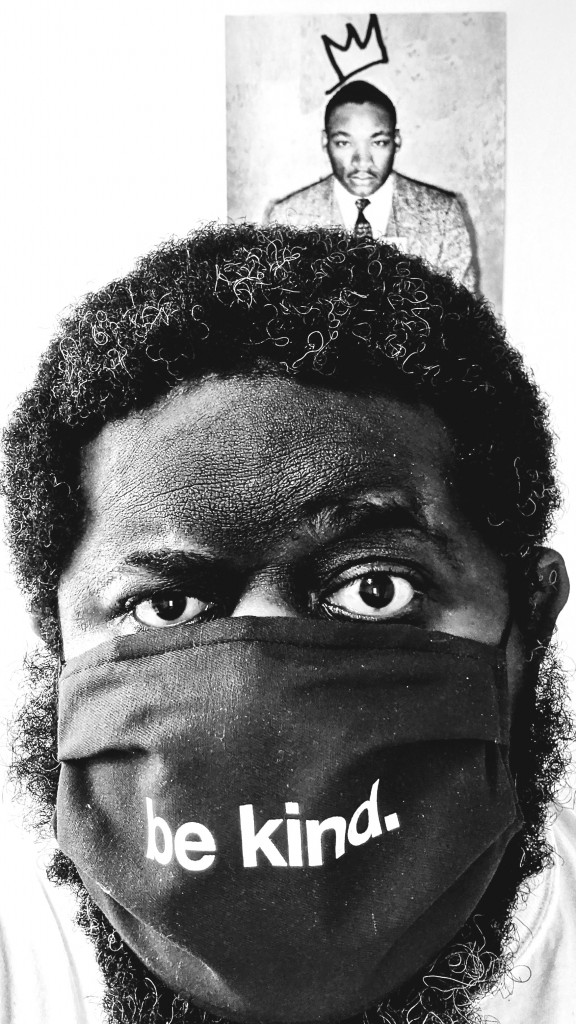

A meditation on hair, its role in Black culture and how society views it

From a single centimeter to about three-and-a-half inches long when it’s straight. Before you ask, I’m not talking about the article that’s been floating around on social media recently in which scientists claim that a recent heatwave is giving men giant “summer penises” (thank God). I’m talking about my hair. My curly, coarse, still-abundant-but-definitely-full-of-gray, ethnic hair. My hair that I dutifully have had someone completely cut off every two weeks, give or take, for the entirety of my life. The hair that’s had flecks of gray in it for as long as I can remember but still grows like a weed. The hair that is so tied to my sense of self that it has been the source of a good percentage of my stress over the pandemic and the resulting lockdowns and quarantines. Not being able to go to concerts, weddings, bars and social events, in general, has presented one challenge. Not feeling safe, not shaking hands or not hugging another person in months is one on another level. On a third, surprisingly personal level, though, exists me and my relationship with my own hair.

You see, in the Black community, hair is not and never has been “just” hair. It’s been a status symbol, a signal of class and style. It’s one of the ways that we express our individuality and creativity as a culture. It’s also been used against us by police and employers for generations. As such, in some households, what hairdo you have is just as much a part of the infamous “talk” that Black parents have with their children as anything else. That’s why for the vast majority of my 34 years on this earth, I have never had more than about a centimeter’s worth of hair on the top of my head. Anything longer than that, and my late grandmother would say, “You’re starting to look like a hoodlum.”

My late mother would say variations of the same thing but add words like “scraggly” or “rough.” She would also admonish that I didn’t want to “give the devil a foothold” by walking around looking like whatever Black person had committed or been accused of committing whatever the crime of the moment was. She cautioned that all some white people would see is: Black, male, nappy hair. And that would be enough to make them react negatively. I remember very specifically when the men behind the brutal killings of Shannon Christian and Christopher Newsom were apprehended during my college years. My mom made me stop what I was doing and get a haircut. The killers were Black males that looked nothing like me but still were within spitting distance of my age, and she wanted me to look as clean-cut as possible to make sure there was no confusion.

I laughed because I was in my early 20s, and, at that age, anything a mom tells a son is sweetly filed under “overprotective” and you move on. I laughed … but I still obliged. Obliged because by then I had already received my fair share of “UT Alerts” (text messages that were at the time sent to the entire student body to alert us to crimes on campus) with descriptions of assailants that read like this: “African American male with black hair, between 18 and 30 years old, standing between 5′ and 7′, weighing between 150 and 300 pounds, wearing jeans and a t-shirt.” It was a description that at the time encompassed approximately 95 percent of ALL of the Black people that I knew, myself included. It was no big deal at the time – just another thing that Black parents tell their kids so that they don’t get undue attention from the police or, you know, random lynch mobs. Tomato, tomato. I didn’t think twice about it at 20-something.

Now, at 34 years old, I live in a world that is beset by a pandemic that makes things like “hairstyle” seem frivolous. Scores of people are dying, Black people at an even higher clip than the rest, from a disease spread primarily during close human interaction. I haven’t been anywhere besides work and my apartment since March 15. I have the very risk factors that would make this disease particularly hard on me – or lethal, even. Every day that I wake up is a new exercise in one of the age-old tenets of my Christian faith: “walking by faith and not by sight.” What is the thing that nags at me daily, though? If not several times throughout the same day? The fact that I haven’t had a haircut since the end of February. For so many years of my life, having a full head of hair that existed as it naturally grows from my head was seen as a sign of no good. As something dangerous. Something that could keep me from getting a job. As something that in the wrong situation could get me killed. That’s a lot to assign to something so small. So … naturally occurring.

When I was an infant, I had an Afro. Long, curly locks that were every bit dark, lovely and commercial-style, I’m-black-and-I’m-proud, let-your-soul-glooooo luscious. I have on good authority that it also made me the cutest thing in existence for the entirety of the summer of ‘86. At some point, though, it went from being a commodity to being a target. I guess the same can be said for the African American experience in general. For a while, it’s cute, something of a novelty to play around with and try on for size in contrast to your regular life. Why just party when you can “turn up?” Why braid your hair when you can put it in cornrows? Why TikTok to Taylor Swift when I can dance to Lil Yachty instead? Black culture is fun to put on when you can take it off whenever you want to. When you can go back to your everyday life when you’ve had your fun.

What happens though when you can’t? When you’re not wearing a t-shirt with George Floyd’s face on it … you look like him. When Breonna Taylor looks like your sister? Ahmaud Arberry: your brother. Elijah McCain: your younger cousin. When you want to think that you’re a grown man, with the same rights as the “you can’t make me wear a mask” people you see on TV all day, living in a society that says you can wear your hair however you want. An advanced, progressive society … in which all of the people I just named were killed in various circumstances by people who didn’t look like them simply because they looked like YOU.

What do you do? You do what people of color have always done: survive. You go about your daily life with your head on a swivel. You thank the handful of hot girls that you know who have told you how much they love to see you growing your hair out for the boost in confidence. You think of your white college roommates and buddies who lost their hair around 25 and thank the ancestors for the good genes. You carry around a brush and a comb and make sure that you look like you give a damn. You live your life. You live your life … but you still remember how the police mistook a similar hairbrush in a young black man’s pocket for a gun during a routine traffic stop and killed him. Progress, forever balanced with remembrance. Outside of searching YouTube for how to cut your own hair, I suppose it’s the only way. Outside of curing racism itself … it’s the only way, I suppose.