Nashville is known as Music City for a reason. Anywhere you go you’re likely to see and hear live music. You can find music of all kinds here – anything from country to rock to folk to pop to hip hop to EDM and more. You name it, we’ve got it. And more often than not, it is really good music. This city is so competitive that it hardly leaves room for the crappy stuff.

Nashville is known as Music City for a reason. Anywhere you go you’re likely to see and hear live music. You can find music of all kinds here – anything from country to rock to folk to pop to hip hop to EDM and more. You name it, we’ve got it. And more often than not, it is really good music. This city is so competitive that it hardly leaves room for the crappy stuff.

One of the most precious things to me in this city is to find myself surrounded by local musicians on a front porch. One after another they pick up an instrument and start jamming. The talent in this town is incredible. There’s a large pool of amazing songwriters here. These “behind the scenes” musicians are responsible for many number 1 hits out there, but their lives are not as flashy as the stars’.

Dave Pahanish is one such songwriter. And today I count myself especially lucky to be on Dave’s sunny porch. His daughter Eva is running around the yard, giggling and bouncing her little 2-year-old bootie up and down, following the rhythm of her dad’s guitar. Dave’s wife Kristin is rocking their newest family addition Lily Miles on her lap, as she chimes in with her beautiful voice. A truck-load full of friends drop by to share a beer on the front porch. A perfectly normal day in the perfectly crazy lives of the Pahanish’s.

Dave was born in Pittsburg, but he grew up all over the place, moving around every three to four years due to his dad’s job. The wide range of music played around his parents’ house included everything from the soundtrack of Jesus Christ Superstar to Chuck Berry’s Greatest Hits to Booty’s Blues. But Dave had a love for classic rock and blues from the beginning.

In 1990 he started to gig his way around the U.S., just going around and playing music in an attempt to make a living – which proved to be very difficult and a financial struggle. But his music started to get placed in TV shows, which led him to a publisher in New York. Starting to see more steady paychecks from his publishing deal, Dave eventually moved to Nashville six years ago in pursuit of a songwriting publishing deal. He has since then written three number 1 hit songs: Keith Urban’s “Without You,” Toby Keith’s “American Ride” and Jimmy Wayne’s “Do You Believe Me Now.”

But this is not to say that this guy is all country. His live performances are incredibly fun and packed full of southern rock with a healthy dose of funk. And if you’re extra lucky, his gorgeous wife Kristin will get on stage and sing her bluesy song for you with that sexy, golden voice of hers. What a treat. Lucky you, you will be able to catch Dave Pahanish (PANFISH) in Knoxville at the Preservation Pub on February 1, 2014.

To help spur your interest and convince you that this show will be well worth your time, here’s my front-porch conversation with Dave Pahanish.

BLANK: How did you end up in the publishing world in Nashville?

DP: I signed a pub deal for Sync Rights in New York because I had a lot of existing albums that they were just taking and throwing them into soap operas and stuff. Then I started seeing money from that, checks from that – they weren’t really much thinking back – but at that time everything over $1,000 was a holy-sh*t-check. And that was the first royalty checks I started getting and I started thinking: “Man, maybe I’ll look into this publishing thing a little bit more,” because I was writing a lot. Essentially I ended up moving here for a publishing deal.

When I started doing showcases in New York everybody thought it sounded like country music, which at that time – at least pop country music – was something I felt very distant from. It felt like an insult. I never really considered myself a country artist. But I figured I wanted to play and sing still. And instead of having to do every f*cking gig that came along, which is a lot of everything and anything, I always kind of wished I could selectively do the gigs that I want and make music that I want. But in doing that you need some type of income that doesn’t distract too much. So I came here thinking if I can’t get a record deal, surely I can get a publishing deal and the songs are at least worth something. And at first I did what probably a lot of people do: just writing for the market and stuff for myself. But as time went on, it just of kind of became a lot of the same thing. The stuff that I was writing was already there, without me really trying – like it already had a pop element. Just not totally country, but I guess country has moved more toward pop. No matter how anti-country or anti-whatever you are, I feel like if you write a really, really good song it will shine through.

BLANK: Do you struggle with writing music that you know sells versus doing what you really want to do?

DP: Yes, it’s kind of like that. I would like to just do whatever the f*ck I want and be able to make a living. It’s just not that way. Especially with something that is beyond money, the value of art…it’s hard to say what is good, what is not good – it’s hard to put a dollar value on it.

It’s very difficult to focus as an artist when there are ties to things…like I have abilities in the music world to do things that aren’t necessarily stuff that I would do. It might almost even seem inconsistent. Because I have an artistry that is kind of the heart and soul of what I do. But the end to that is not always…it’s not financial. So it’s hard to gauge success on something…the stuff that’s most important to me is the stuff that makes no money. If it starts making money, if I start working toward that, it becomes something different. Different motivation, you know. So it’s always been difficult for me to do interviews. For instance this particular interview is all about fueling people’s interest in our upcoming Knoxville show. But there’s nothing really newsworthy when someone is just talking about a show. I get conflicted, I start answering questions as if my art is something that people…I mean how would you even know unless someone heard it? It’s all based on personal experience. But the success I’ve had as a commercial writer for other people – it balances one another out in a way. It’s not a sob story. It’s just the conflict is always within me.

BLANK: What has been your biggest challenge in the music business and how did you overcome that?

DP: THAT is the biggest challenge, and I still have not overcome it – which is doing uncompromising work and trying to be an artist to push the envelope and also make money at the same time. Like how do you entertain without trying to entertain somebody? That’s still the conundrum, you know. But I have opted, personally, to just try to separate the two.

When I first came to town, like I said, they met at a crossroads. I was doing stuff that was artsy and that was fulfilling me – not really, but at least at that time – fulfilling me as an artist. But in trying to get a record deal before I came to town, I was already starting to alter music to make it more…but at the same time I found a sweet spot. Before I moved to town it was kind of like it had all the elements of pop and it was about as far as I was willing to take it, but it seemed to hit home with a lot of people – especially in Nashville for whatever reason. So I started coming down here seven or eight years ago to check it out. And I saw a couple of artists play in town. I saw Jeffrey Steele play an acoustic set, and at that time I think he was the songwriter of the year. It was just very interesting to see him. He’s just f*cking awesome. He’s a great singer. He’s got his own thing, you know. To put it in a nutshell, there were tunes that I had heard on country radio that I despised, which was just about everything. But there were a couple I especially didn’t like. And then I came down here and I saw him play these same songs on an acoustic guitar in his own way and I saw where they came from and all of a sudden they made sense. You know what I mean? That it wasn’t always the song, it was the messenger that was getting in the way for me. And it still does. The artist itself makes or breaks the song, whether it works or not. At least when he does it, there’s a true artistry to what he does. I think he went down a different path that was more toward following the trends than that of an artist, but it was enough to show me that you could skate the line between art…you could still find a way so that part of you is yourself, but that will also sell to the masses without selling out.

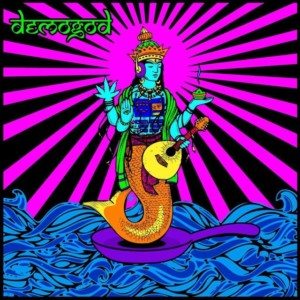

BLANK: You have a new album out: Demogod. What were your inspirations for that album?

DP: My inspiration for that album was a lot of stuff from when I first started recording and playing music in the late 80’s/early 90’s. I had a four track recorder and I was really drawn to it. There were things I would be able to  do on a four track but when we took them into a studio and tried to recreate the pop version of it, it killed it. And I never understood what that was all about. And for a time I liked listening to lo-fi music, I still do. And bands like The Folk Implosion, Lou Barlow and stuff. I listened to a lot more of that. Demogod is a throw back to those early days of my writing and recording…but it’s just a collection, a mish-mash of everything from 80’s new wave, punk, blue grass, just all the music that I love filtered through that four track sound. That’s what I was going for.

do on a four track but when we took them into a studio and tried to recreate the pop version of it, it killed it. And I never understood what that was all about. And for a time I liked listening to lo-fi music, I still do. And bands like The Folk Implosion, Lou Barlow and stuff. I listened to a lot more of that. Demogod is a throw back to those early days of my writing and recording…but it’s just a collection, a mish-mash of everything from 80’s new wave, punk, blue grass, just all the music that I love filtered through that four track sound. That’s what I was going for.

BLANK: Who were some of the people that worked with you on this album?

DP: I did most of the parts myself. But Leroy Powell, of course, played some guitar parts on it. He’s played a lot on my last three albums. Kristin Lee, Steve Wolf, and just a little bit of people here and there, just little small parts. For the two albums before that I’ve mainly employed and used our circle of friends, which is one of the things that makes the albums more special to me. I tried to do it all very organically. That’s what I like, that’s what I’m all about as an artist. The opposite of the commercial because doing it with money as your intention kind of steers you away from it. But regardless, I like to keep it organic, so it becomes kind of a testament or document of everything that’s happened here. Like the tunes on Time, there was stuff that happened so spur of the moment – I had the mikes set up here at the house and Gitano (Herrera) walked in once in the middle of a tune I was mixing and was playing guitar behind me and it sounded so good that we added it in. And I like that about those albums, about the music on them, that this whole community that affects me so much becomes a part of it.

BLANK: Tell me a little bit about your involvement in the songwriting community, for example Open Road Mondays at the Building and PANFISH Wednesdays at Dan McGuinness and Panfest, too. What’s your motivation to do all those things?

DP: We’ve only had one Panfest so far, but we may do another one. This is all the stuff that I wish I could do for a living. That’s the artistry side. That’s what gets me off the most: the spontaneity and making the most out of the moment. It makes every night kind of like a work of art, you know? The special vibe is different. And that’s the reason I got into music to begin with, that type of energy. On Monday nights at the Building I don’t play, but I just like the idea of there being a scene, like a place where the whole night is a singular work of art. Anything can happen, you know? And me just running sound back there, I do that in a way that…I feel like it brings the best out of a lot of people. I may change the space or make it appropriate to someone’s sound…like if one guy goes up and he’s playing a certain kind of way and doing things a certain way I would run sound for him differently than for someone who’s going for something else. It’s like creatively trying to figure out how to bring out their best. And at times I don’t exactly hit what they’re trying to go for, but it doesn’t really matter. For whatever reason, those nights are just about the moment. And it’s good release for me. Same thing with Wednesday nights at Dan McGuinness. Wednesdays are our night and my band PANFISH always plays. And for the other bands we book, we try to get something different, but bands that also have a draw so they can be exposed to what’s going on there.

BLANK: What are you hoping to get out of these events? Do you have an idea of what you would like it to grow into?

DP: I would like it to be something that we can sustain our livelihood to live off of. I want to do what I’m doing artistically – I want that to be all about the risk-taking and all about the stuff that is not sentenced down. I want that to be the niche. Because if that’s the niche then I can just consistently push the envelope and search and just enjoy being in it and also not have to worry about the pressure of changing or modifying or compromising it to be able to make money. Such a whiney story. I just want to do what I want to do, when I want to do it. And yeah, I want people to like it! But I don’t want it to be about people liking it. They seem to dig it because I dig it, you know? Not me as a person, but it’s like watching someone surf. They can’t be focused on anything but the moment and enjoying it. So as a spectator you can get off on that. Imagine how does it feel to be inside that wave? So…I just want to be a professional surfer.

BLANK: How are you received outside of Nashville? Is it hard to break out of the Nashville market?

DP: I don’t go away much. But when I do, I usually come back 10 feet taller. You get used to a certain standard when you’re in town, of excellence, for lack of a better word. But I mean musicianship, all the stuff that you take for granted just to stay above water, you have to be at a certain level. So when you go outside of town, I always feel like – especially when I go back home – your head could get big. Very well respected, just off the grid, outside of the norm. All good things. And that feeds on itself. Last time we traveled as a band, I did four shows in two days, but we did our Wednesday night thing at Dan McGuinness before we left and I seriously felt like I could have flown or had levitation at that last show. It’s like the energy level and everything just clicking, you know? And the last place we played is where I used to live. No matter how I look at myself, back home people see me as a success, you know? They base it on achievement. I’m successful to some respect.

BLANK: What’s your advice to someone who’s coming to Nashville to make it as a songwriter?

DP: It all depends on what they’re trying to do. I talk about success and stuff like that. I know what’s expected or kind of what’s expected to write hit songs in this town. And I try to bypass all the…not make it so complex in that arena. I feel successful as an artist, in the sense that I finally found something that I feel like is mine. And that’s why it means so much to me. The stuff I’m doing now is closer to what I did when I first started that had nothing to do with money. Because I never thought I’d be able to make a living playing music. I was just happy to have music, to be able to write a song I was proud to show people. And that’s where I’m at now. And once you reach that level it’s very difficult to accept the stuff that you’re not proud of, or jump on the manufacturing line and start putting out bullsh*t after bullsh*t, because that is what a lot of people are listening to. But as far as being an artist, I’d just tell them to just play what you like. Maybe that’s the best advice.