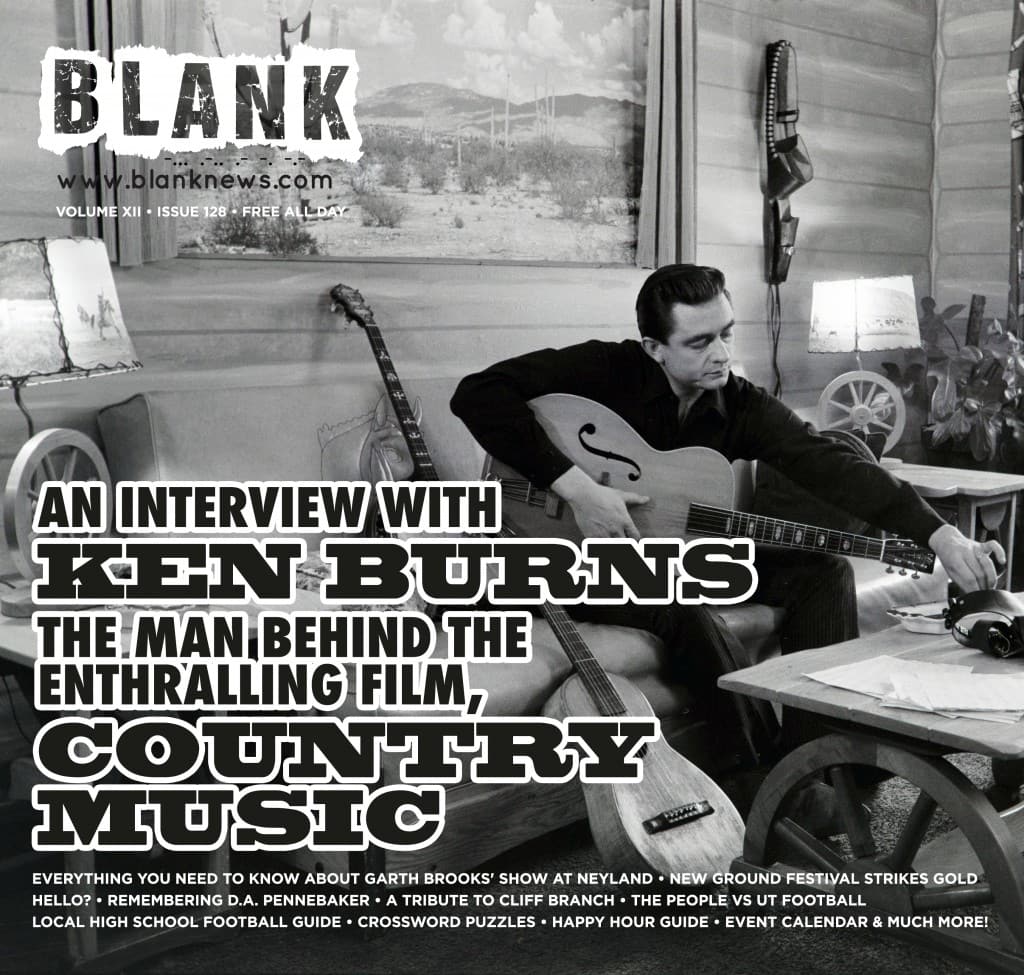

‘Country Music’ traces genre’s storied roots

Ken Burns and company tell history with a human connection

There’s a certain expectation to a Ken Burns documentary. Since his five-part series “The Civil War” became a must-see event when it premiered on PBS in 1990, his work is expected to be compelling, dramatic and definitive.

So when Burns and his team turn their attention to country music, it is an event that is particularly special for East Tennessee. Bristol, after all, is where what has been called the big bang of country music occurred in 1927 when the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers made their first recordings, and Knoxville is the place where many country music legends, including Roy Acuff, Chet Atkins and Dolly Parton, honed their skills before moving on to Nashville and international stardom.

The 10-hour, eight-episode series “Country Music” premiered on PBS on Sept. 15. Earlier this year, Burns, writer/producer Dayton Duncan and producer Julie Dunfey stopped in Knoxville and Maryville as part of a promotional tour for the series. After documentaries about jazz, the national parks, baseball, radio, World War II, the Vietnam War and a host of other historical topics, its creator says that tackling country music was a natural next step.

“Country music is American history firing on all cylinders,” says Burns. “I’m always looking for great topics that reflect us. And that ‘us’ is both the lowercase, intimate one and the U.S. Nothing could be firing on more cylinders than country music because it’s such an elemental, direct way of expressing human emotions, which all of us have.”

Burns says work on the series began in 2012, and it began to grow in scope over the ensuing years. The team’s researchers and producers utilized photos and film from both The Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol and the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound in Knoxville, as well as families of country artists and other individuals involved in country music.

“When we started off, we thought it was going to be six [episodes], and then it was seven. And at a very late date for us in the process, when we were still working on the script, we decided that we had to divide our sixth episode into six and seven. And that is because of the amount of material we got and how we tell stories.”

Credit: Bristol Historical Association

Duncan says that there were plenty of stories to tell within the series, many of which were surprising to him. One involves the Carter Family when they were performing on XERA, a Mexican station across the border from Del Rio, Texas, which broadcast at up to 1 million watts (as opposed to the 100,000-watt limit imposed on radio stations in the United States) and could be heard on both coasts and all the way into Canada. A.P. Carter and Sara Carter had divorced by this time, and Sara’s boyfriend had moved from Virginia to California, never answering her letters over the course of several years.

“One night on the radio she says, ‘I want to sing a song, and I’m going to dedicate it to Coy Bayes,’” says Duncan. “It’s this great song, ‘I’m Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes,’ and 1,200 miles away or so, on the far side of the Sierra Nevada, listening to this border-blaster station is Coy Bayes and his family. When he hears that, he looks at his mama and says, ‘What happened?’ And she admits that she had been hiding the letters that Sara Carter had been writing him, so he had given up writing her. And this is a revelation that she still held something for him in her heart. So he goes, ‘Mama, I’m gonna go get Sara.’ And he got in his car and headed out. If you wrote that in a screenplay, you’d be laughed out of the room, but it was true.”

In addition, radio station XERA was owned by “Dr.” John Brinkley, who saw radio as a way to get rich – which he did.

“He sees it as extension of the old medicine shows where a quack doctor would use music to attract an audience and then sell them some snake oil,” says Duncan. “In his instance, it was rejuvenating men’s sexual potency by implanting goat testicles into them. You can’t make this stuff up!”

And then there’s omnipresence of the aforementioned “I’m Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes,” the tune from which also was used for “The Great Speckled Bird,” a song with which Roy Acuff wowed the audience during his first appearance on the Grand Ole Opry. It later was adapted to Hank Thompson’s “The Wild Side of Life,” which was then answered with Kitty Wells’ “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” which also used the same tune.

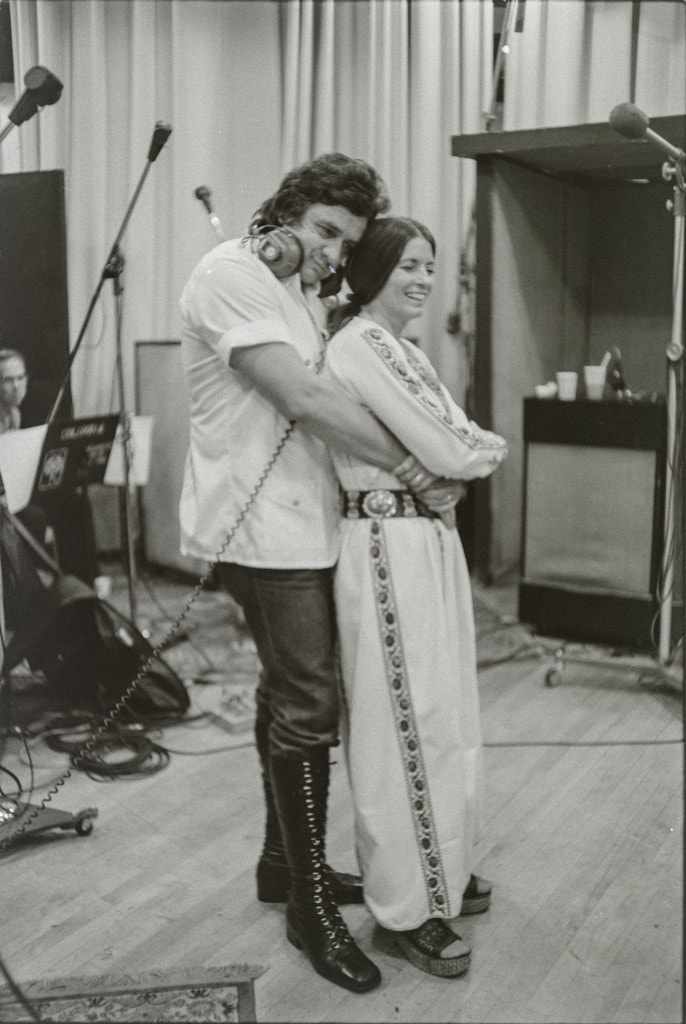

Credit: Les Leverett Collection

It’s the personal stories that make history more interesting; here, the filmmakers, Duncan says, illuminate a bigger picture by exploring these smaller anecdotes.

“How did we pass along the memory of what had happened before in pre-literate times and early-literate times?” says Duncan. “It wasn’t by listing dates and facts and names. It was by telling stories. That’s how you remember things. If you ask someone to tell you a little bit about their life, they’re going to tell you a story. That’s because that’s how we try to organize our memories.”

Dunfey says everyone with whom she worked in East Tennessee was welcoming and helpful. In particular, Eric Dawson with TAMIS helped locate Cas Walker show clips and archival scenes of Knoxville, and he connected her with the families of performers.

Although Dunfey was somewhat familiar with country music before the project began, she was surprised to find what a huge role women have played within the genre since its inception.

“When you’re starting country music and the growth of it as a business, it’s Mother Maybelle and Sara Carter right from the get-go,” says Dunfey. “And then it’s the Maddox Brothers and Rose, and then Kitty Wells, and when you hit the late ’50s and ‘60s and ‘70s, it totally explodes.”

Photograph by Les Leverett

Loretta Lynn made waves with what might be considered the first true feminist hit songs, including “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)” and the even more direct “The Pill,” in which the singer says she’s going to cat around just like her partner because now she has “the pill.”

Dunfey says filmmakers showed a rough cut of the episode featuring Lynn to group of people in Hanover, New Hampshire, while the series was still being put together.

“A friend of mine brought his 17-year-old daughter at the last minute,” says Dunfey. “The daughter didn’t want to come. She wasn’t interested in country music. I got a letter from him the next morning, and he said, ‘My daughter went home and downloaded every Loretta Lynn song she could find and is telling all her friends the story of ‘The Pill’!”

Of course, Dolly Parton is also featured prominently.

“She’s in a lot, and she deserves to be in it a lot,” says Burns. “The centrality of her story is without equal. I’m not willing to say she’s the most important person [in country music], but I’d be hard-pressed to say there’s a more important person. Maybe Hank Williams. I don’t know how you’d make that decision. The stuff that she’s written … ‘Jolene’ and ‘I Will Always Love You,’ tell me something better than that. ‘Jolene’ is just a phenomenal piece of music.”

For those who know their country music history, the series is refreshing in that it connects jazz, blues and R&B with country. In Knoxville, Chet Atkins, Homer and Jethro, Don Gibson and others all were listening to the Hot Club of France, as was Willie Nelson in Texas. And, as is pointed out in the series, jazz and R&B artists were listening to country, too.

“The industry of it takes on the erroneous presumption that the only people listening to country music are white people and the only people listening to R&B are black people,” says Burns. “But then how do you explain Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley? How do you explain Ray Charles coming out with ‘Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music’? It means that, as Wynton [Marsalis] says in our film, art tells the way of us coming together in a way when our culture sometimes reverts to the simplistic tribal instincts. We’re in a period right now where we need country music more than ever.”

The series also makes the connection to blues and how its black artists influenced white stars.

“If you took the Mount Rushmore of country music – A.P. Carter, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, Bill Monroe and Johnny Cash – all of them had an African-American tutor, someone who took their chops from this level to this higher place,” says Burns.

It’s the human connection, the ability to tell a human story, that makes classic country music what it is, says Burns.

“Story is at the heart of what country music does,” says Burns. “It distills the essence of human emotion and human experience, so our job was just to paint the gigantic kind of complicated Russian novel: multi-generational, dozens of characters creating this great story.”

Credit: Sony Music Archives

Although Burns and his team made the most complete history of country music that they could, he has no opinions on the state of country music today.

“We’re in the history business,” he says. “That’s a kind of dangerous territory right now because there’s a lot of people who are upset that country music has become so commercial and so dominant and what they consider country music is now called Americana or roots. We have the luxury of being historians. We stop in the mid-90’s with Garth Brooks’ ascendancy and the death of Bill Monroe, and we tie it together with the death of Johnny Cash and his last years. And we look at some of the people today, but we’re not jumping in. We don’t have the authority as historians to judge people in the near past.”

“Raised In Knoxville,” a podcast hosted by Todd Steed that focuses on the history of local country music, in connection with the “Country Music” series, is available at www.wuot.org.