Deep Listening: “We Build What we hear in our mind”

Pauline Oliveros passed from this life to whatever follows it on Thanksgiving Day, 2016. At 84 years old, she was the matriarch of the acoustic philosophy which holds aloft all that is encompassed by Knoxville’s remarkable Big Ears Music Festival. In a world drowning in nonpoint source musical pollution, she will be sorely missed.

It is right and fitting to consider the impact of Pauline Oliveros in the weeks and months before the 2017 edition of Big Ears begins. That’s the space-time she occupied most comfortably, the moment before the music begins. It is that moment Pauline brought to the attention of a culture awash in new ways of imagining, making, recording, sharing, hearing and listening to music.

There’s a difference, you know, between hearing and listening. This was Pauline’s favorite point to share.

Put yourself in the best seats in the house, in the best concert halls in the world. Carnegie Hall, the Tennessee Theatre, the La Scala opera house…The curtain hasn’t opened yet. 100 musicians are in the orchestra pit, warming up in that deliciously random cacophony where everyone is testing their instruments’ tone and tuning, each one expressing its respective voice. Then the conductor taps his baton on the stand and lifts his hands. The orchestra hushes and comes to attention. And in the second or two between that tap of his baton and the first note of the symphony about to begin, the world hangs in suspension. Every sound ever heard and every sound possible in the future is there in that moment. It is a presence unlike any other. It is the instant before the Big Bang. It is where Pauline Oliveros discovered what she called “deep listening.” And “deep listening” is what Big Ears is all about.

Pauline was the avant garde before the avant garde knew it existed. In the early 1960s, she discovered the universe of possibilities waiting in the magnetic heads and exposed reels of an AMPEX tape recorder, the vacuum tube warmth and signal generator patch boards of prototype synthesizers and the ever-lovin’ freedom of San Francisco at the now legendary Tape Music Center, where she was an early collaborator.

It was legendary back then, too. Pauline’s experiments at the TMC attracted the attention of everybody who was anybody in the nascent California rock and jazz scenes… if not the artists themselves, then their producers, live sound engineers and recording masterminds.

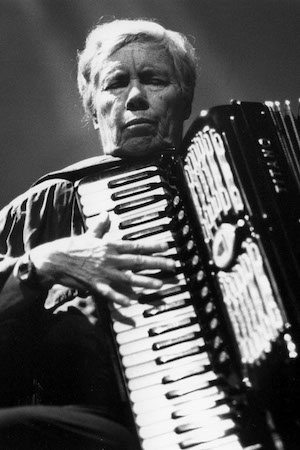

Not bad for an accordion player. But if you need evidence of how not like Lawrence Welk’s her music was, check out Pauline’s “A Love Song” on YouTube sometime. It is five minutes of the most hauntingly lovely presence I’ve ever heard.

Presence. This is an important word to consider. The type of presence I’m talking about is actually a filmmaking term. Before a scene is filmed, before a single line is spoken, a film production team’s sound recordist will call for absolute quiet on the set and then order “roll sound.” Every mic to be used in the subsequent scene is turned on, and – for a minute or two – the sound of the set itself is recorded. The sound of silence. That’s presence. And in post-production, when the film’s soundtrack is mixed, the addition of the recorded presence of every scene’s environment is critical to giving dialogue, action, music and effects a basis in reality… a natural reality.

In 1988, Oliveros discovered the power of presence in a concrete cistern at Fort Worden, an abandoned military facility in Port Townsend, Washington.

The cistern stored water to fight fires that might have threatened Fort Worden’s artillery batteries. The fort was part of the defensive “Ring of Fire” built at the turn of the century on the northeast tip of the Olympic Peninsula to protect Puget Sound, the maritime gateway to Everett, Seattle and Tacoma.

Just saying “cistern” doesn’t conjure the reality of this space. It is a subterranean circular tank, almost 200 feet in diameter, 14 feet from floor to ceiling, capable of holding more than 2 million gallons of water. Its ceiling is held up by concrete columns, spaced 15 feet apart.

The cistern’s shape, dimensions, volume, columns and composition give it a sonic quality that is absolutely astounding. Reverberations from any sound made in the cistern can last as long as 45 seconds. And when the cistern was visited by Oliveros and two cohorts (vocalist Peter Ward and trombonist Stewart Dempster), it gave birth to a compositional and performance philosophy that is at once obvious and concealed. Their recordings from the cistern serve as a landmark achievement in modern sonic arts, as riveting as early Gregorian chants in the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, and as spiritually focused.

A year after Oliveros unlocked the “deep listening” secrets of the cistern, the avant garde genius John Cage wrote “Through Pauline Oliveros, I finally know what harmony is… It’s about the pleasure of making music.”

As steady and incisive in her eighties as she was in her twenties and thirties, Pauline Oliveros was among the first to adopt and adapt every technological advance in music making and sharing that came down the pike, often before anyone else knew what was happening. That’s what it means to be avant garde, but few artists of any medium can sustain that description for their entire lives. In this respect, Oliveros was quite like Pablo Picasso, who famously observed “We don’t grow older; we grow riper.”

I met Pauline in the early 1990s in Austin, Texas, when she was collaborating with another sustaining giant of the avant garde, dancer Deborah Hay. I had just been technical director for performances by Hay and a large ensemble of non-dancers, chronicled in her book “Lamb at the Altar.” And I arranged to rent Pauline’s house in Kingston, N.Y., while she was in Austin for a year or two and I was pursuing a project in New York City.

We talked one morning on the back loading dock of a now-gone arts studio called Synergy before she spent an hour playing her accordion alone in the dark. The loading dock was about 10 feet from the Missouri-Pacific / Amtrak line that runs through Austin. She asked me about a videotape I had made with John Cage a dozen years earlier for the DIA Foundation, in which Pilobolus founder Moses Pendleton and I spun LP-sized video discs across a tile floor like hula hoops you spin backwards so they’ll return like boomerangs, taped in a time before VCR users knew that digital discs existed. This was for a Cage disquisition on future media.

But as I started talking about meeting Cage, a train approached slowly, trailing more than 100 tankers and boxcars. I stopped mid-sentence as the 4-engine powerhouse went by, and it took more than 20 minutes for the caboose to pass us. The entire time, Pauline never budged. She just stared at a spot on the tracks that made every set of passing wheels shriek slightly. For more than 100 cars. The rhythm was hypnotic. And her concentration said everything.

At Big Ears 2017, I hope you have the opportunity to listen that deeply.

Pauline Oliveros now blesses the silence she occupies, a silence that gives breath to every performance on this year’s line-up. Make beautiful noise for her.