Two decades after ‘Where You From’ put East Tennessee on the hip-hop map, Mr Mack is still building a culture … and doing it his way

By Steve Wildsmith

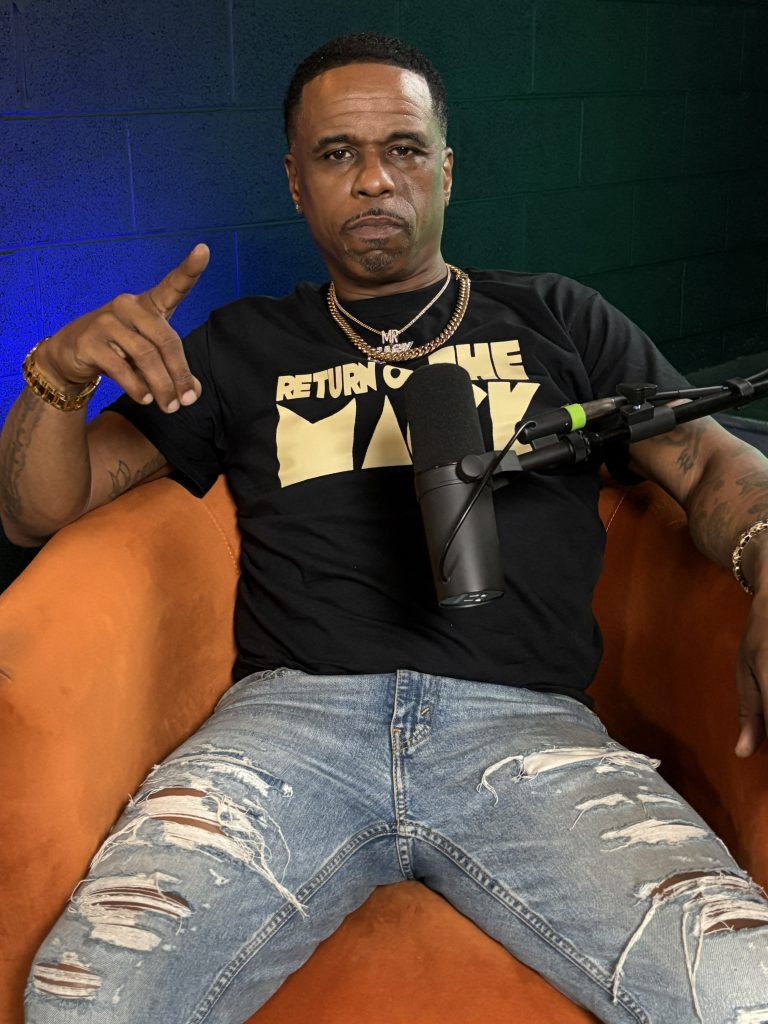

It’s a rainy, gray, late-November Friday morning, 15 minutes before “Mack in the Morning” is supposed to go live on Facebook, and the man himself, Leroy Mack Williams aka Mr. Mack, has yet to arrive.

His young protégé, Kaden Lyons, is already behind the boards, preparing for what will be the 277th episode of the morning show that’s become a touchstone for Knoxville urban culture, hosted by the man whose career-defining hit was a literal anthem for it.

“Where You From (Da 865)” wasn’t Mack’s first song, but it was the one that launched him toward stratospheric success – and sent him crashing back down to earth just as hard. Given that meteoric rise and phoenix-like resurrection, he’s not sweating the clock when he cruises through the door, feet thudding down a narrow staircase to the studio, checking in on Lyons before heading up to his office.

It’s a preshow ritual that will not be rushed – not indulgence, but preparation. The rolling of the smoke is part of Mack’s process, a moment of calibration before he steps back into the public eye three days a week. Wednesday’s “Mack in the Morning” theme is, naturally, “Wake N Bake Wednesday” (as opposed to “Mackin’ Mondays” and “Freestyle/No Filter Fridays”), and guests are welcome to partake if they choose. For Mack, it functions less as spectacle than as an aperitif – no different, really, than the glass of cognac poured before a long conversation or the cigar lit by any other captain of industry settling in to regale supporters of his latest conquest.

For Mack, that conquest is the first genuine body of work designed as and put together as an album: “Return of the Mack,” a love letter to fans that its creator believes is sacred. He’s got plenty of material in the vaults, and hip-hop is encoded too deeply into his DNA to ever stop making music altogether, but another record?

“Honestly, I’m just here to push it to my fans, and if we get some new ones along the way, great,” Mack says. “I’m at a point in my life where music ain’t the sole object anymore. If we can get some new fans, that’s dope, but it’s my last album that I’m going into the studio to do.

“I don’t want to work on another album for eight or 10 years, you see what I’m saying? I’m gonna drop singles that I’ll make in the studio, and I ain’t saying I’m leaving music. Let’s be clear about that! And there will be more albums coming out, because I got so much music on the hard drive, but as far as going in, creating a body of work and sticking to this subject? It probably won’t happen again.”

He will, however, continue to help the scene – and the musicians who populate it – make their own work, and that’s the biggest difference between the Mack of 2025 and the upstart young rapper he was in 2006. Back then, he was mesmerized by the smoke and mirrors of a music industry that signed him to a contract before promptly shelving him.

The “Where You From” fame lasted a good while and made him connections that still pay dividends today. But this studio and the equipment in it – the shows and the podcasts, the cast of characters who seek out his Svengali guidance and Midas touch – are the product of hustle. No label executive, no record-industry insider, will ever dictate the terms of his ambition the way they once did.

“On ‘Return of the Mack,’ they’re going to hear about the struggles of a dude who pretty much lost everything, but now he’s back, and he’s taking what’s happened to him and using it to show love and support other people and lead by example, you know what I mean?” he says. “It’s a lot of Mack you know, and a lot of Mack you don’t.”

And it’s currently for sale on CD only – for a jaw-dropping $100.

Mack grins when asked to confirm that price tag, and he doesn’t stutter.

“It’s for my fans, man. It’s for the people who really, really fool with me,” he says. “My cousin actually talked me into doing this, because at first, I didn’t believe it. Didn’t believe I could. I was like, ‘Man, I ain’t doing that.’ Ain’t nobody gonna fool with me like that, but I was being naïve and scared.

“I stepped back and took a look at where I’ve came to, where I’m at now and what I’ve built, and it’s like, ‘Yeah, you can do this. And you’re gonna do it!’ It’s a dope body of work, and it comes with a T-shirt and a QR code where you can upload the album to your phone or wherever, so you don’t even have to listen to your CD, because I know for a lot of people who still buy them, they’re like collectibles and antiques. So that way, you scan the code, the album pops up, and you download directly to your phone.

“I know some people are probably like, ‘A hundred bucks? That’s crazy!’ But there are people willing to pay that because they want to hear what we’ve been doing,” he adds. “And in some ways, that makes it even more special. You know, it makes it even more valuable because it’s like, you know, anybody can go to Walmart and get a $10 or $20 CD. But this most definitely ain’t that.”

“Return of the Mack” won’t be found on Tidal, Spotify, Apple Music or any other streaming service, either. It’ll be a while, he says, before it’s uploaded to those platforms, ensuring that the fans who pony up the $100 have exclusive listening rights for the time being. A couple of singles from the album are already out, with another on the way, but for now, Mack’s focus is on building “Return” into something closer to a relic: rare, coveted and deliberately out of reach.

“This is something specific, something special,” he says. “I’d rather have a hundred supporters than a thousand followers, you know what I’m saying? I’ll take those hundred people any day.”

Those fans – the metaphorical hundred who number far more across the sprawling urban culture that exists in the shadows of East Tennessee’s music scene – have been with Mack from the beginning. It’s a harder, more street-savvy form of rap and hip-hop that gets little mainstream love but serves as a prolific breeding ground for talent that inevitably finds its way to Volunteer Sounds, either as paying customers or as guests on “Mack in the Morning.”

They’ve been riding with him since before the fame, back when he was just a country boy from Rockford.

Growing up, Mack attended schools in the Blount County system – places like Eagleton and Heritage High School, often viewed with condescension by those who went to the county’s city schools in Alcoa and Maryville. That caste system still exists today, but for an ‘80s kid who had already seen more of the world than rural East Tennessee, it wasn’t going to define him.

“My mom and dad had family in Atlanta, Canada, Chicago, Detroit, and my daddy didn’t mind getting up and driving there,” he says. “My granddaddy didn’t mind getting up and driving to go see that family for a week or a weekend, and they would take us with them. So I saw a lot. I saw clothes earlier, so I had things before they were popular, even in high school. I was wearing jewelry even back then.”

For his senior year, Mack transferred to Alcoa High School. At first, he was viewed as the country bumpkin. Then he started rapping.

Someone cued up a beat, and the narrative shifted.

“It was a lot back then, being in some of those places, and I wasn’t always the one that was accepted at first,” he says. “I always kind of had to fight my way through if I was going to get accepted at all.”

Mack Williams, as he was known at the time, has never shied away from a challenge. Throughout high school, he rapped and deejayed pep rallies at both Heritage and Alcoa, and by the early 2000s, he was pressing homemade mixtapes into the hands of anyone who wanted one.

By then, hip-hop had exploded into national prominence, and in a perverse echo of the Reformation, record labels dispatched executives southward in search of young Black artists who might make them a fortune.

By 2006, Mack already had several projects under his belt, and “Where You From (Da 865)” fit squarely into the call-and-response party-rap energy of crunk, the dominant sound of the era. He knew he had something special when friends tried to buy the song outright the moment they heard it.

“I had a couple of people … when they heard it, they were trying to buy the song from me,” he says. “But I knew what I had, and this one … it all started because I’m from Blount County, and Blount County and Knoxville hasn’t always mixed. I mean, I was just a Rockford country boy, but I had conquered this little, small area here in Blount County.

“So how do I get bigger? I can’t just say I’m from Knoxville, even though I’ve got tons of family over here. So how do I get people on board? You scream out the area code, which is for everybody. It ain’t about a city, or a neighborhood, or a project; it’s for everybody.”

Mack’s manager at the time got the song on “Listen to My Demo,” a segment that ran on Knoxville’s urban contemporary radio giant Hot 104.5 (WKHT-FM). Deejays played 90 seconds of songs submitted by aspiring artists, and listeners would call in to vote on which ones deserved full-time airplay.

“Where You From” hadn’t reached the one-minute mark before the phones started ringing. The station eased it into rotation, two or three times a day at first, but it wasn’t enough for listener demand. Carefully calculated performances at places like the Red Iguana (now the Old City Sports Bar, above Southbound) provided proof to fans that Mack was as good onstage as he was in a studio booth, and suddenly Hot 104.5 was playing “Where You From” a dozen times a day, if not more.

“Where You From” vaulted Mack out of East Tennessee and into a national conversation at precisely the moment the music industry was scouring the South for the next breakout voice. Radio spins multiplied. Industry attention followed. Meetings were booked. For a rapper who had spent years hustling mixtapes by hand, the validation felt tangible, earned and inevitable.

A major-label deal followed.

On paper, it was the breakthrough every independent artist dreams of: resources, reach, legitimacy. In practice, it was a lesson Mack would never forget. The song was hot. The moment was real. But the machinery behind it moved slowly, cautiously and often without explanation. The same industry that had rushed to claim him proved just as quick to lose interest.

The phone calls slowed. The momentum stalled. What had felt like a launch began to resemble a holding pattern – one Mack had no control over and no clear timeline to escape. Eventually, the deal dissolved. The machine moved on. Mack was left behind, carrying the weight of expectations that had been raised and abruptly abandoned.

It was a familiar story in hip-hop – talented artist, regional hit, major-label interest, quiet disappearance – but living it was something else entirely.

In retrospect, casual fans saw it as a puzzling vanishing act: a flash-in-the-pan brilliance by a guy whose banger catapulted him to the No. 1 sales spot at the Disc Exchange (long gone now, but a mecca for music lovers back in the day) and kept him in the Hot 104.5 top five for nearly three months. Then, nothing.

Mack sees it differently.

“Everything that can be given to you can be stripped away from you just as quickly,” he says. “I pretty much got shelved. It’s just the typical rapper story. And from there, I was broke. I had no money. I didn’t have a studio – nothing. I had to rebuild. I had to keep going.”

The fame lingered longer than the support. “Where You From (Da 865)” remained a calling card, a song that opened doors and started conversations. But the infrastructure that was supposed to sustain a career never materialized. Whatever safety net Mack thought he’d earned vanished with the contract.

What followed was survival.

Without the backing of a label, Mack did what he had always done: adapted. He leaned on relationships, built new ones and found ways to keep moving forward in an industry that had already taken its shot at him. The dream didn’t die; it hardened. He did what he needed to do to get by, choices he doesn’t romanticize but that still carry weight in a culture that values lived experience over myth.

Over time, he developed a sharper understanding of power, ownership and how quickly both can disappear. There was no glamour in that life, and it wasn’t one he wanted – for himself, or for his son, Jae LeQuan Williams, who briefly followed in his father’s footsteps and charted his own modest Hot 104.5 hit, “She Gotta Crush on Me,” at just 10 years old.

Mack cycled through a string of low-wage jobs to keep food on the table, devoting every hour outside of work to rebuilding his career, this time with the infrastructure in place to ensure that progress, while slower, would be permanent. Boiler Room Entertainment positioned itself early on social media. Mixtapes followed. Collaborations stacked up, both with national names and with artists still grinding for recognition. A dedicated fanbase emerged – one drawn not just to the beats, but to Mack’s bars and his refusal to disappear.

In 2012, Mack released “Clash of the Titans,” a mixtape that included a feature from Three 6 Mafia co-founder Juicy J. It was a reminder that, even outside the industry machine, his reach and credibility remained intact.

Around that same time, he collaborated with a then little-known rapper from Middle Tennessee who went by the name Jelly Roll. Their track, “Tennessee Roads,” which also featured Skwirl, captured something both artists understood instinctively: Southern identity as lived experience, not branding.

It wouldn’t be the last time Mack’s instincts proved prescient.

As Jelly Roll’s career exploded onto the national stage, the collaboration stood as another quiet marker of Mack’s role in the ecosystem – not as a gatekeeper chasing trends, but as an artist who recognized authenticity early and moved accordingly. Long before viral moments and crossover success, Mack was already building connections rooted in shared geography, shared struggle and shared respect.

For him, it was never about chasing the spotlight again; it was about building something that couldn’t be taken away, which is why he’s been sitting on another Mack-and-Jelly collab … until it came time to put together “Return of the Mack.”

“Honestly, it was a song that we did back in the day. He’s rapping on this – it ain’t the country-singing Jelly Roll! It’s a song called ‘Country S*it,’ and from the beginning it was my plan to hold that song for ‘Return of the Mack.’”

By 2016, Mack had put together enough bread to buy a mower and some weedeaters, and he launched a lawncare service that endures to this day.

“I do want to get some more mowers and a hydraulic truck, but I want a team, because I’m not cutting grass!” he says with a laugh. “I’m done with that. This is where I belong now.”

He gestures to the unfinished ceiling lapped by rolls of insulation, black-painted walls emblazoned with the “Mack in the Morning” logo and the show’s standard décor. The online studio is a recent addition to Volunteer Sounds, which first opened in 2018 on Alcoa Highway. Needless to say, the never-ending construction along that particular thoroughfare necessitated a quick relocation.

“I did a year there, and then we were working out a plaza when I was like, ‘I need something standalone,’” he says. “I was talking to a friend who hooked me up with my current landlord. He took me to a spot that was further out west, and I boomed out of there for about another year until I needed something bigger.

“He was in this spot and was like, ‘I’ll move out of this, and you can get it and it’ll cost you this amount of money. I came out and took a look at it, and I was like, ‘Yeah, I love it. This makes sense.’ And we’ve been here five years now.”

One of the little eye-catching things scattered throughout Volunteer Sounds are single Post-it squares hanging from the bottom frames of computer monitors, on the fridge in the kitchen, to the side of the soundboard in one of the control booths. On it is a single figure: “$10,000,000.”

It’s a reminder, Lyons says, of the next financial mark that Mack intends to hit.

“Ten million, that’s what he’s looking at, all the time. That’s what he wants. That’s to get everybody in the same mindset,” says Lyons, who started out as an unpaid intern learning the ropes on the “Mack in the Morning” show. His father used to dabble in the rap game back in the day, and when his son expressed an interest in both making and recording music, he pointed Lyons toward Volunteer Sounds. Like a herb-smoking hood Yoda, Mack took him in, and today Lyons is a paid studio executive earning his audio engineering degree at Pellissippi.

“One of the biggest things I’ve learned is that you’ve gotta have multiple streams of income,” Lyons says. “I mean, if you look around here, we’re set for podcasts, for recording, for space to give other people their shows. He’s got his own music, and merch, and then he hangs TVs, and … “

He turns, gesturing toward two words in white lettering on clear glass, backlit from within a black frame: “Hustle Harder”

“… it just f***ing defines that.”

And it’s not done – not the studio, and certainly not the vision. As far as the studio goes, Mack credits his mama that it’s even open at all. He would have continued to build, to refine, to set up, until his mother, he recalls, reminded him that he was burning through money too quickly.

“If I would have waited till my studio was all the way finished and how I wanted it, I’d never have opened,” he says. “She says, ‘Son, you gotta open. The longer you take, the less money you’re making. You’re paying rent on a place you ain’t even opened yet, and it’s supposed to be a place that’s making you money! You gotta open!’”

And so the work continues. Every single thing in Mack’s life is a work in progress, because he’s never satisfied with “good enough.” Wherever the top is, he’s not there yet, and when he gets there? When that $10 million threshold is reached? Those Post-it notes will be replaced with new ones and another figure. $25 million, maybe. Or $50 million. Until they, too, are eventually replaced.

“I’m trying to be a hood Ted Turner, man,” he says with a laugh. “I want to produce shows for young artists and for young people. It’s like I tell my artist North Olive [a young female rapper making waves with the singles “Knoxville” and “Eat It Up”], ‘You need a show! You can’t just rely on the rap!’

North Olive. Hardaway 1K. Yung Honcho. Playmaker. TPG FLAME. Tiff Terintino. King Ali. These are the up-and-comers making waves as Mack did almost two decades ago. The young hustlers and grinders he salutes, along with another dozen that he hesitates to leave off the list.

“I really can go on and on and on, and it’s still going to be like, ‘What about me?’, you know what I mean?” he says. “It’s just so many names, just a lot right now that I’ve seen come through, and you can see the energy and the passion in them and the want and the drive. Some of them lack different things, but so did I back in the day. What matters is whether they’ll acquire those things as time goes on.”

Of course, it helps if the scene has the support structure to give the culture an outlet. Knoxville has long been notorious for being leery of hip-hop shows, and local venues that feature it on a regular basis … or, in some cases, every weekend, as other live music clubs offer rock and country on Fridays and Saturday … aren’t exactly mainstays. At the moment, however, there are a few places where fans can connect, support and enjoy the music of homegrown talent, including The Velvet Room at 2514 Martin Luther King Jr. Ave.; Club Mangos at 8705 Unicorn Drive; The Birdhouse Community Center at 800 N. Fourth Ave. in the Fourth and Gill neighborhood; and, on occasion, The Pilot Light, 106 E. Jackson Ave. in the Old City. Barley’s in the Old City brought Devin The Dude and Masta Killa to its stage over the past couple of years and local favorite J Bu$h just had his album release show at the venue, as well.

Like making music, performing it has to be just one more piece of the overall concept. The world has become too digitally dependent and interconnected these days, and musicians have to be entertainers if they plan on making their art into a career.

“And that’s coming from somebody who never had a Plan B. I just kind of opened another business within my business,” Mack adds, gesturing to vending machines both upstairs and down, stacked with snacks and drinks that, given long hours in a studio booth and an entourage with plenty to smoke in the downstairs lounge (where there also happens to be a PlayStation 5), become much-coveted commodities among his clientele.

And the gear? Don’t get him started. There’s easily $100,000 worth of recording equipment in the studio, but Mack sought out most of it via Facebook Marketplace. Some of it’s been restored; some, like the Neumann U87Ai Condenser Mic, were purchased new because, as a client of Volunteer Sounds as well as being the owner, he had no intention of putting down “Return of the Mack” on amateurish equipment.

“I experienced it. I lived through it, so I have a right to talk about it,” he says. “I have the right to speak what’s on my mind, whether it’s racism or mixed relationships or whatever,” he says. “That’s the one thing I wanted to get across in this story, is that there’s nothing off limits when it comes to Mack. No matter what happened, I’m going to tell the truth, because that’ll always take you further.

“I’m not ashamed of nothing. Shame, man … I don’t need that in my life. Everybody’s done been up, and everybody’s done been down. Everybody’s lost sh*t, so I’m never ashamed of nothing like that. I’ve had artists tell me, ‘Yo, Mack, you’ve made it! I wanna be you!’ And yeah, that’s great. I just haven’t made it to where I want to be. Am I successful? I get up every day, and I do what I want to do. That sounds like success to me.”

wildsmith@blanknews.com